This little flower has reappeared in the last month or so, an irrepressibly cheerful sight this dark time of year. It’s a composite flower of the Asteraceae family – so named for their similarity in form to stars – the outer female florets sporting a long strap petal, and the inner male florets being simple tubes. The colours range from yellow into orange, emphasising the individuality of each one. It’s an annual which is supposed to flower all year round – hence its Latin name, from the Roman Calendae, the first day of each month – but here it seems to die back in the summer heat. It’s an annual, having to regerminate from seed, which is easier in the autumn rains. It’s also a rapid coloniser of cultivated, ploughed land so it often appears here at the edges of vineyards. The scientific name is probably more familiar than those of most plant genera because of its healing properties, although most products seem to be made from the cultivated marigold, Calendula officinalis. It’s anti-everything: antifungal, antiseptic, anti-inflammatory etc. Why ‘marigold’? Because as a healing plant brought from the Mediterranean to northern Europe in the Middle Ages it was named in honour of the Virgin Mary, to distinguish it from other, non-therapeutic ‘golds’ such as chrysanthemums.

Its name in French is Souci des champs, souci usually meaning a worry or concern. That doesn’t seem the right name for something pretty, long-flowering and healthy, and in fact it is the wrong interpretation: souci in this context comes via old French soulsie from the Latin sol sequia, meaning sun follower, because the flowers open in sunlight.

Flowers are the stars in front of the camera in the recent David Attenborough series, Kingdom of Plants, which was shown on Sky I believe – I was lucky enough to be given the DVDs and some kind of report on them is well overdue. As you may know, the series was made over the period of a year in Kew Gardens: here’s the man himself introducing it:

In the films, the flowers really take the starring roles: there is exquisite time-lapse footage of petals of every shade and size unfolding, the largest being the Titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum), a flower seven feet tall:

The strong points of the series for me were the photography, and Attenborough’s awareness of the interdependence of the whole natural world: bats needing nectar, flowers needing to be pollinated, fungi exchanging nutrients with green plants, and so on. But I can’t help being in two minds about the films, as I am about Kew itself. I haven’t got a TV so I was the more taken aback by the relentless search for an exciting visual, and hence the focus on flowering rather than any other plant process. And the ‘making of’ feature brought home to me how in some ways the sheer tonnage of high-tech equipment deployed began to dictate the film: if something could be done, with an expensive gadget (3D cameras, booms, robot helicopter cameras) for the first time ever, then it HAD to be done.

I only have a vague memory of going once to Kew with my parents: I just recall a lot of rhododendrons. In the films Kew itself is ever-present, constantly lauded and never questioned, given a respect that even deities don’t enjoy these days. It is a fascinating place, but it fills me with very mixed emotions. On the one hand I agree with the superlatives: it does have over 40,000 plants actually growing there, while I think I’ll be lucky to see half the 2,000 or so species growing near my home – present count is only about 120.

On the other hand: maybe it’s a kink in my personality, but I always want to puncture inflated reputations, deserved or not. Kew Gardens have undergone several metamorphoses since their origins around 1720 as private pleasure gardens for the royalty whom Britain imported from Hanover after the Act of Settlement, and with whom the country is still saddled. Kew is still a ‘Royal Botanic Garden’. As with many botanic gardens, it served initially as an ego-project, each prince and king in Europe vying to have the greatest number and the most exotic species. The cost of botany was high and many plant collectors died: Captain Cook’s 1768-71 Pacific voyage in the Endeavour cost the lives of 38 crew members, and Joseph Banks, the botanist (and later Kew adviser) who went with him, lost five of his eight staff while amassing 3,600 dried plants.

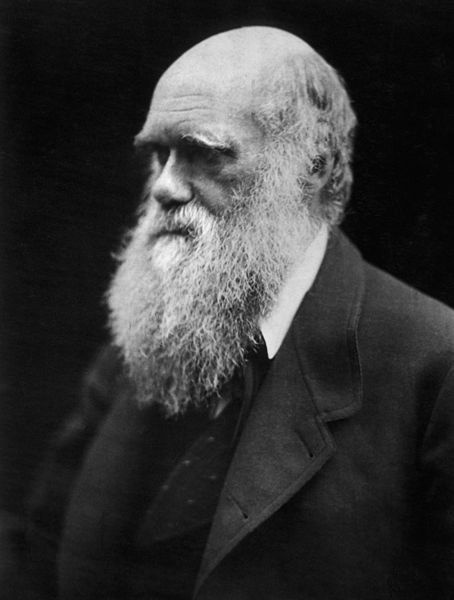

Kew began serious collection of plants targeted for the needs of the British Empire in the 19th century, transporting from one continent to another tea, rubber and many other plants – for the benefit of the colonial planters. We forget what the lifestyles of the Victorian upper classes were like. For example, in 1868 Charles Darwin and his family went to the Isle of Wight on holiday, renting a cottage from the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, for whom he sat for a portrait.

Her family lived solely from the proceeds of their coffee plantations in Ceylon. While coffee had originally been brought there by the Dutch (who had stolen plants from Mocha in Yemen), it was Kew who stepped in with Liberian varieties in 1873 when a quarter of Ceylon’s plantations were wiped out by disease. Darwin’s own private income came mostly from his tenant farmers and railway shares.

I’m realising that the history of Kew is too full and too interesting to cover here, including as it does much of the history of botany itself, so I’ll come back later to these and other themes, including a bizarre minor skirmish in the battle of the sexes. The reinvention of Kew in the last century has been as a scientific institution – although that’s not obvious from its website (here), which presents it as a jolly public attraction. But I’ll give credit where it’s due: the scientific work behind the scenes is invaluable, and is mentioned in the Kingdom of Plants. I’ll mention just two projects: the first is the use of its vast herbarium, which includes over 8 million specimens and covers 90% of all known plant species, to compile an internationally accepted list of named plants. The results are online at theplantlist.org (click to go there) and are available and indispensable to people like me, as well as to professionals.

The second is the Millennium Seed Bank, an effort to conserve indefinitely supplies of seeds from all over the world to protect against extinction and catastrophe – here’s the Kew video about it:

The last words are from David Attenborough:

The truth is: the natural world is changing. And we are totally dependent on that world. It provides our food, water and air. It is the most precious thing we have and we need to defend it.

I thought I’d celebrate the flower as star with two stars of the music scene in France: the New Orleans-born Sidney Bechet wrote and recorded the tune Petite Fleur in France sixty years ago, in 1952. You’d like to hear it sung in French? Pas de souci – seven years later the singer and guitarist Henri Salvador, born in French Guiana, recorded a popular version, with French lyrics by Fernand Bonifay, and here it is:

Because it’s winter and this post is about a garden, here’s a song Salvador recorded on one of his last albums, Chambre Avec Vue (2001), when he was 84. But this time it’s sung by Stacey Kent: Jardin d’hiver.

Coming up soon: Trying out a new camera, and seasonal colour.

I’ll be looking out for this series, I hadn’t heard of it before reading this, thanks. I know what you mean about Kew, it always seemed very pompous! However it’s done a good job of reinventing itself over the years and also becoming a viable business, it is sometimes too full of visitors. I lived in London for 10 years and it was always a great place to escape from city life although I’ve probably visited more often with my kids since leaving London (Kew always has lovely exhibits for kids).

Watching the DVDs again, I see how much natural history is in there, though thanks to DAs effortless delivery you almost don’t notice that you’re learning science. I would love to go to Kew for a first visit as an adult, and the glasshouses look amazing as architecture. I’m glad you feel it’s a good escape from the city life – when it first opened to visitors in the 19th century it was in the country, and it was debated whether people would travel that far out of town.