Art In Conversation

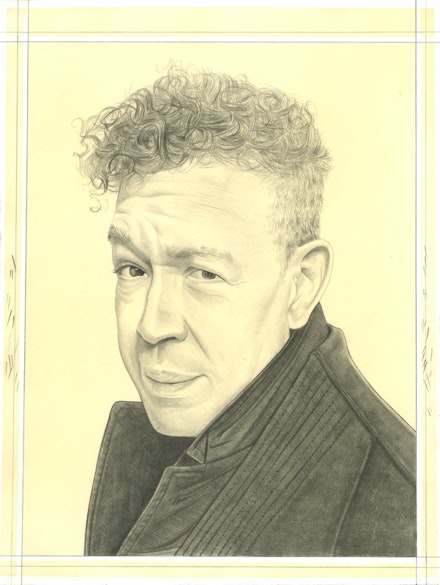

ANDRES SERRANO with Eleanor Heartney

Andres Serrano gained international fame—or some would say notoriety—in 1989 when his photograph Piss Christ became embroiled in the battle to defund the NEA. The work is a cibachrome photograph that presents a crucifix glowing through a luminous orange-yellow field of light. It was created by shooting a small plastic crucifix that had been submerged in a tank of urine. Culture warriors in Congress and the religious community focused on the fact that the NEA had provided a small sum of money for its exhibition at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. They charged Serrano with blasphemy, sacrilege, and obscenity and transformed Piss Christ into an emblem of government corruption and art world decadence. Over the years Piss Christ has continued to ignite controversy and is periodically attacked and defaced when it is publically exhibited. Meanwhile, Serrano has continued to create beautfully crafted, provocative photographs that touch on such themes as faith, sex, death, homelessness, race and bigotry. His most recent work, currently on view at the Station Museum in Houston and starting September 28 at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York offers an exploration of torture. For this series, Serrano traveled to concentration camps, a Stasi prison, and various torture museums. He also created re-enactments of contemporary torture scenarios, in some cases employing actual victims of torture. Here he talks with Eleanor Heartney about torture, power, religion, faith, and his own artistic history.

Eleanor Heartney (Rail): How did this new work come about?

Andres Serrano: In 2005, I was asked to do an assignment for the New York Times Magazine about Abu Ghraib. I did a few images, including one of a hooded man that appeared on the cover. After that I forgot about it and went on to other things. Then ten years later I met Andrei Tretyakov. He is a collector based in London who founded an organization called A/Political. They fund socially conscious work. Andrei asked me if there was anything I would want to do that they could help me with, and I said, ‘Once upon a time I started this torture series but I never developed it. Are you interested in that?’ He said “Yes, definitely” and that’s how it all came about.

Rail: So the original piece was made in 2005. But when you returned to the subject ten years later in 2015, the whole thing began to have a different complexion.

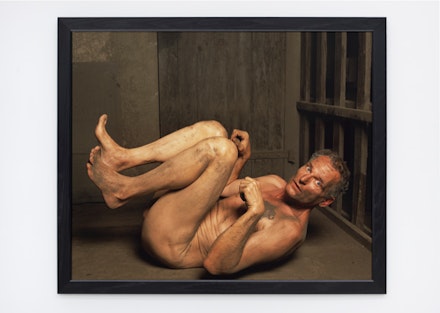

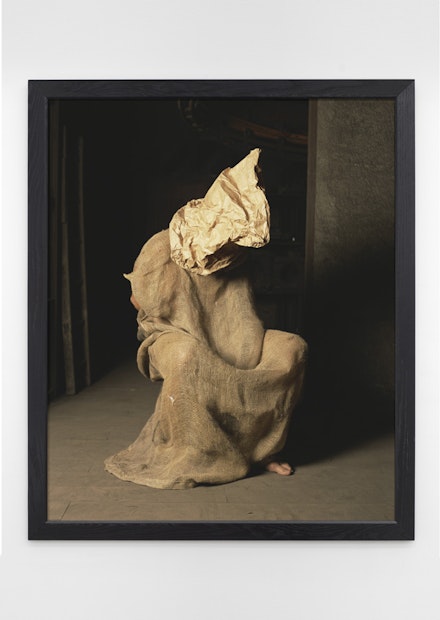

Serrano: Now I took it seriously. Thanks to A/Political I was able to spend three months in Europe in 2015, exploring different ideas and looking at torture from many different perspectives, including torture as a tourist attraction. I went to a number of torture museums. Most of them have reproductions of torture instruments, but I did go to Hever Castle in England which has real torture instruments from the 16th and 17th centuries. I also went to concentration camps and Holocaust memorials. Lastly, I developed a series of scenarios based on hooded men. Most of the hooded people I photographed were reenactments I did at a place called The Foundry in Maubourguet, France. It’s a former foundry that has been turned into an artist residence by an artist named Andrei Molodkin to whom I was introduced by A/Political. I did many of these torture scenarios in a factory that had once manufactured arms and munitions but had been abandoned for years until Moldokin took it over. I was lucky in that I was the first artist to do some work there while the space was still in a pretty raw state. Since then they’ve renovated and made it more suitable for living quarters, although the main space is still pretty much the same.

Rail: So it was perfect for you.

Serrano: It was perfect for me because the buildings were full of thirty or forty years worth of dust and objects. I envisioned The Foundry as an imaginary black site where I could create imaginary scenarios. In addition to the reenactments I did at The Foundry, I also photographed real torture victims, notably the Hooded Men of Ireland, a group of fourteen Irishmen accused of being IRA agents by the British authorities in 1971. They were imprisoned for about two or three weeks during which time they were tortured and brutalized and always had their heads covered in hoods, which had a lasting traumatic effect on them. Thanks to A/Political who arranged my visit to Belfast, I met four of the Hooded Men: Francie McGuigan, Brian Turley, Patrick McNally, and Kevin Hannaway.

They are now in their late 60s. I wasn’t interested in photographing them as individuals, but as The Hooded Men, so I brought hoods with me. I spoke with the men for thirty minutes, and then I asked them to do something that they never thought anyone would ever ask them to do: I asked them to put on the hoods. They were shocked and it took a few minutes for them to consider my request. But they took a deep breath and did it. It was a traumatic reliving for them. But they realized that I was an artist, that I was serious, and that I was in their corner, meaning I would do anything I could to bring more attention to their cause. The Hooded Men were subjected to what are now known as the five techniques of interrogation. They are still in court with the British government over their treatment and are represented by human rights attorney Amal Clooney. Although I’m not a political artist, I’m always happy to shed a light on social causes and the human condition.

Rail: Did it feel different photographing real torture victims rather than re-enactors? Did you approach them differently as a photographer?

Serrano: Well, that’s the thing. I always say I’m not a photographer. I’m a conceptual artist with a camera and this is a case in point. If I was a photographer, I’d be taking their portraits, but I had no interest in that. I was not interested in photographing four individuals. I wanted to photograph the Hooded Men, and the Hooded Men could only be the Hooded Men if they had hoods on. In these works, each individual is identified by his name. This is what separates the Hooded Men portraits from the reenactments of hooded men I did at The Foundry. You know these are the real guys because the titles are their names.

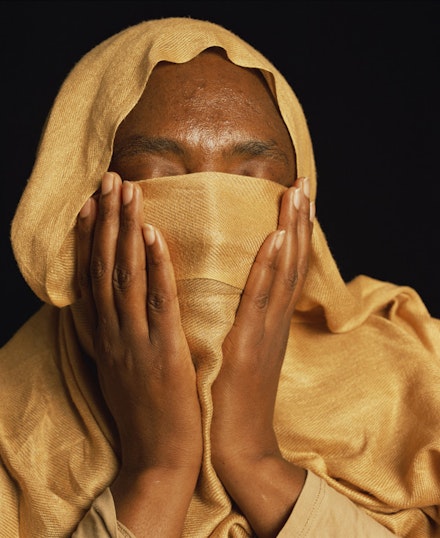

I also photographed a woman from the Sudan named Fatima, who is also a real torture victim. She was abused and repeatedly raped by the Sudanese police. When I came to take her picture, she didn’t really want to show her face, so I suggested we cover her face up to her eyes and she was okay with that. Again that was ideal for me because I would rather turn the portrait into something else rather than a straight portrait.

Rail: You’ve done a broad survey of torture through history. But how do you define torture? That was such a big issue in the Bush era and continues to be one today. Is waterboarding torture? How did you deal with that issue?

Serrano: I didn’t think about the definition of torture. I thought about the people under my control. It’s easy to torture people when you have power over them. Maybe that’s the definition of torture. I had power over my models. They gave it to me willingly, but even in these recreations, even when it’s only role-playing, I noticed it was difficult for them to hold some of those positions. Imagine if it wasn’t make-believe, if it was real torture and they had to hold these positions for hours instead of fifteen or twenty minutes, imagine how much more painful that would be. The definition of torture is the ability of one human being to inflict pain and humiliation onto another.

Rail: Your images made me think of the similar power dynamic in Santiago Sierra’s work. He is known for performances in which he pays people minimum wage to do humiliating and degrading things. They are willing to do it but it often creates an ethical quandary for the audience. In one performance, he had Iraq war veterans stand motionless in the corner of a museum gallery all day. In another one he paid prostitutes in heroin to be tattooed across their backs. He has people do pointless and nonsensical things. Partly it is about a power relationship, but because these works are done in art contexts, it’s also a reminder of the audiences’ double standards. People are disturbed about the Iraq war veteran getting minimum wage to stand in a corner, but meanwhile the museum guard nearby is also getting minimum wage to stand around all day. It’s one of the ways Sierra pushes people’s buttons.

Serrano: I met Sierra at The Foundry. We were talking and he said something about “niggers.” And when I said, “you know that word is not acceptable,” he answered, “I know, I was just testing you.” That’s what he does. He likes to test his audience.

Rail: Do you get involved in that kind of thing? Do you see your works as a test of your audience?

Serrano: Not at all, because frankly I don’t give a damn about the audience. If the work pleases me, that’s what matters. I’ve always seen myself as both the artist and the audience. I’m not trying to provoke anyone, I’m trying to challenge myself as an artist and make it interesting for myself.

Rail: But torture is a very provocative subject at this political moment. You started this series in 2015, which was before Trump announced his candidacy, but during the campaign Trump brought the issue forward with his support of torture and promises to bring back waterboarding. He was saying things that even the most fervent conservatives didn’t feel they could say. Did that play into your approach to this subject?

Serrano: I wasn’t paying attention to what anyone was saying. I like to think my work is both of the time and timeless. The work resonates then and now. Things don’t go away, they come back. Take homelessness for instance. I did “Nomads”—portraits of homeless people—in 1990 followed by pictures of the Ku Klux Klan the same year. In 2014, I did the “Residents of New York,” another series of homeless portraits and in 2015, the “Denizens of Brussels.”

In 2004, I photographed Donald Trump for my “America” series. I created that work in response to Sept 11th. It was my vision of America. I photographed more than 100 people from all walks of life from 2001 to 2004 for this series. I photographed firefighters who’d been digging through the rubble, I photographed police, soldiers, an airline pilot, an F.B.I agent in a hazmat suit, a postal worker, a Reverend Canon, working class, middle class, rich people, poor people and famous people—celebrities like Snoop Dogg, Yoko Ono, Arthur Miller, Russell Simmons, Anna Nicole Smith, John Ashbery, Ethan Hawke, and Donald Trump. I chose Donald Trump because he was a businessman extraordinaire and because he was Donald Trump. Then and now, he meant something.

Rail: Like torture, the culture wars are another thing that was dormant and now is back. You were one of the iconic figures during the culture wars of the early 1990s. Do you find yourself in the crosshairs again this time?

Serrano: I’m not in the crosshairs, but I got some flak for a show that was in the Station Museum in Houston, Texas. It had some torture, Trump’s picture and a Piss Christ.

Rail: What are they protesting? Is it you, or the work?

Serrano: It’s Piss Christ. Piss Christ hasn’t been shown in this country for a while. One of the things that bothers me is that I’ve had about twenty major museum shows in Europe in the last twenty years, in France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Northern Ireland, Hungary, Croatia, Poland. Even Australia. I’ve got an exhibition coming up at the Petit Palais in Paris in October. By contrast, aside from the Station Museum, I’ve only had one museum show in America. That was twenty-five years ago—it started at the ICA in Philadelphia and went to the New Museum and other places. Station is a private museum, so they don’t give a damn about funding. It bothers me as an artist that I can’t get a museum show in America because they’re afraid of my work and I’m not a flavor of the month. I’ve never even been in a Whitney Biennial. My work’s been included in a couple of shows as part out of someone else’s installation. But I’ve never been an invited artist to the Biennial. It used to bother me but now it’s a badge of distinction.

Rail: Is that about political pressure or funding?

Serrano: I think it’s about lot of things. People ask me, “Do you get censored?” I don’t get censored; I just don’t get asked. It’s a different kind of censorship, like you don’t exist.

Rail: I want to talk about how this work relates to your other bodies of work. What links do you see between say, the fluid series, the morgue series, the shit series, and this new work? Is there a connective thread?

Serrano: It makes sense to me in that I try to find beauty in the unacceptable, the things that people don’t consider fit for art, or even polite conversation. It’s the same reason I did “Residents of New York” a few years ago at the invitation of More Art as a public art project. I photographed homeless people and put the images up at the West 4th Street subway station. I was sick of all these ads trying to sell me something. There were a couple of posters explaining what the project was and there were lots of names on one of the posters. Someone asked me, ”Are those the names of the donors?” I said “No, those are the names of the homeless.” I’ve always been attracted to things that are outside the norm but are part of us. It’s like the emperor’s new clothes. Everyone’s looking at the emperor but no one is saying the emperor has no clothes. So I come along and say “I see a lot of homeless people.” The work is about the things I see that are obvious to me.

Rail: I’ve always thought that this notion of taking the thing that is reviled or disgusting and making it beautiful is very Catholic.

Serrano: I’m very Catholic. I’ve always said I was born and raised a Catholic and that I’m still a Christian. I don’t really think of myself as a Catholic. But recently Pope Francis made a reference to “imperfect Catholics,” those Catholics who are not perfect, but are still part of the Church. He said that we should embrace and accept them. So now I think, I’m not only a Christian, I’m an imperfect Catholic!

Rail: Pope Francis is one of the things that makes this iteration of the culture wars different from the last one. Otherwise, you have many of the same players and many people taking the same positions. These very conservative Catholics and Christians are coming out again against homosexuality, abortion, now even contraception, debating whether health insurance should be allowed to cover that because it’s offensive to them.

Serrano: And of course the immigration issue. They are saying “These people aren’t Christians, why should we want them?”

Rail: Right, the idea is that we are a Christian nation. But one thing that seems to tilt it differently now is that we have Pope Francis, who is making it very uncomfortable for a lot of these culture warriors.

Serrano: Pope Francis has championed the poor. I’ve photographed the poor. He’s been to Jerusalem and Cuba. I’ve done work in Jerusalem and Cuba. He’s been to China. I’ve been to China. Thank God for Pope Francis! God has given us someone to lead us. Without him, we’d be lost.

Rail: The other aspect of your work that seems very Catholic is its focus on the body. Your work always takes it back to the flesh in some way. The works with the fluids, the sex series, the morgue works, and now torture are all about that. Elaine Scarry has written about the way that, in torture you are reduced simply to a body. Your torture series, like the rest of your work, seems to me wrestle with the question: “What is the body and what is its relationship to the spirit?”

Serrano: Christianity is based on the body and blood of Christ. It’s not some abstract thing. The body is very important. Without the body you can’t have the spirit. It’s also a part of reality; it’s something everyone can see and relate to. I’ve never made art about art. Even when I did something like Milk/Blood [a work from 1986 which depicts side by side rectangles of milk and blood] and refers to Mondrian, it’s still not necessary to know a lot about art to understand what is going on. The body is something we can all understand, even if we know nothing about art.

Rail: In the same way you could say that people understand torture because they understand pain. Your torture work raises the question: can art create sympathy for the tortured? Pain is something only the tortured person feels. Can art make a bridge between victim and viewer? I’m thinking of other artists who have dealt with torture. For instance, when Leon Golub painted Latin American mercenaries, the focus was on the torturers who looked directly at the viewer. Botero’s paintings about Abu Ghraib focus on the victims, but he made them, like your torture works, beautiful. In his work and yours there are references to Medieval and Renaissance art. In your case, do you hope that this work will create a kind of bridge between the viewer and the body that is being tortured?

Serrano: No, I think the bridge is between the victim and the torturer. In a way I had to identify with and play both roles, especially that of the torturer. That’s why I say it’s easy to torture people when you have power over them. I think there is a little bit of a torturer in all of us. I’m not a crusader. If I were I’d be in another line of work. I look at it this way. Is the artist a good guy or a bad guy? Even if you have opinions, you can’t show them.

Rail: But people sense them.

Serrano: Yeah, a lot needs to be left unsaid.

Rail: You don’t give us an image of the torturer because you are the torturer. And we, standing in for the artist, are also the torturers.

Serrano: When I was doing this body of work, there was a whole team. Sometimes I felt like I was a director, directing a movie. When you’re a director, even if it’s a harsh reality, it’s still make-believe. Sometimes people confuse movies, or even more, photographs, for the real thing. That’s why Piss Christ was so difficult for people. It felt real even if it was not.

Rail: That’s the difference between your torture work and that of Leon Golub or Botero. Those are paintings, so there is an element of removal. In the ‘90s culture wars, a lot of the problems revolved around photographs. The big controversies involved you, Robert Mapplethorpe, and the photographic insets in David Wojnarowicz’s collages. It was the photographers who were really being targeted.

Serrano: Yes, if Mapplethorpe had painted his pictures, or if I had painted my pictures, it wouldn’t have had the same effect. That’s the power we have as artists. I want to say one thing about Leon Golub. Even though Leon was a great artist with great convictions, he was also a guy with a great sense of humor and a great laugh. If you didn’t know Leon you’d think he was only this serious political artist. He was that and more than that. That’s the thing about great artists—you can’t pin them down to be one thing or another. They’re a lot of things.

Rail: At the same time though you create photographs, all of your work is very informed by the history of painting.

Serrano: I studied painting and sculpture at the Brooklyn Museum of Art School when I was seventeen, and only afterwards picked up a camera. I always say that everything I know about art I learned from Marcel Duchamp, who showed us that anything, including a photograph, could be a work of art.

Rail: And yet your work is so unlike Duchamp’s, in that it is so beautiful.

Serrano: I think Duchamp’s work is also beautiful.

Rail: But there is a retinal quality to your work that he disavowed.

Serrano: Well, that’s because I believe in the art of seduction.

Rail: So you do care about the audience then, because you are seducing them!

Serrano: I do, but I seduce myself first, and then I seduce them. But it’s true, I try to make my images beautiful. That’s part of the contradiction and the problem that people have with my work. You can’t really get mad at the image. It’s something else.

Last election night, on November 8th, I was in Paris giving a lecture. The last photograph I showed was of Donald Trump. Afterwards, there was a discussion. Usually I leave the last image on. As I started having a conversation with the moderator someone in the audience said, “Can you put that image away? Put on Shit, put on anything else.” In fact, it’s a very nice photograph, but it’s the idea that offends more than the image and in that moment, the audience did not want to see that image.

Rail: Maybe now Donald Trump has become the horrible, degraded thing we don’t want to see, at least within the art world. Which brings us to another point. Your work has always received a very different response inside and outside the art world. Or maybe even between different groups within the art world.

Serrano: I don’t know. In the art world I feel I’ve been in and out. I’m part of the art world. My work is in lots of collections, and I’ve sold a lot of work. But I feel there are a lot of things I’m excluded from. It’s ironic. Next month in October I’ll be appointed a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters, which makes me a knight in France. In this country, I’m nothing more than “a controversial artist.” Thanks to my French dealer Yvon Lambert, I’m in the French national collection. They have thirty or forty of my photographs, and they explained that they will always be in the collection of France. Lots of artists and musicians, like Josephine Baker who went to France and Jimi Hendrix who went to England, had to leave America to make it. So sometimes American artists aren’t appreciated in their own country.

Rail: Do you think the American art world’s problem with your work has to do with its overtones of religion? Unlike France or Italy or other European countries, that’s something American intellectuals feel very uncomfortable with.

Serrano: It’s ironic if the American art world doesn’t want to come near me because it believes I’m a Christian, while a lot of people outside the art world think I’m not a Christian. I keep getting letters preaching the Gospel to me, telling me why I’m a bad person, and why I should repent. I get it from both sides.

Rail: If the American art world has a blind spot, it has to do with religion. That makes many curators, critics, and artists uncomfortable. They would rather see artists clearly denigrating religion, which is the thing people outside the art world think you are doing. But in fact, you are doing something much more complex. You are not condemning religion, so the American art world doesn’t know what to do with you.

Serrano: It’s funny because there was a time before the 17th century when the only art that mattered was religious. It’s ironic that now not only is religious art not in favor, but anything looking like it is suspect.

Rail: Have you found support for your work outside the art world, say among less conservative religious people?

Serrano: Yes, in fact, Sister Wendy defended me. I think she said something like, “He’s not such a clever young man but at least he tries.” That was funny. But she defended me. I’ve had shows in churches in Europe and I’ve been asked to speak at the Yale Divinity School. So a lot of religious people have recognized me as a Christian artist and don’t have a problem with my work.

Rail: What do you think they are getting out of your work that others aren’t?

Serrano: They look at it without suspecting me of blasphemous intent. They are just looking at a beautiful image. The fact that the photograph shows a crucifix in piss is beside the point and the title doesn’t offend them. I always title my work in such a way that you—the audience—know exactly what you are looking at. If it’s milk, blood, or piss, that’s the title. When I made Piss Christ, it was piss, it was Christ; so I called it Piss Christ without thinking about it. The people who understand that it’s not meant to be sacrilegious see it from the same the point of view as I do, that everything that God created has to be used and is normal. It’s part of life and God gave us life to enjoy.

Rail: I don’t think Sister Wendy could have put it better! We talked about how you define torture. I’d like to know how you define a Christian.

Serrano: I define a Christian as someone who believes in God and Jesus Christ. That’s it. There are so many different dogmas, so many different sects of Christianity, and so many different ways of worshiping and praying. You can’t say there is only one way to do things. Over the centuries, the Popes and the Catholic Church have changed their minds about protocols and rituals, and even over sins. When I was a kid, it was a sin to eat meat on Friday. One day the Pope decided that was no longer a sin. That kind of shocked me. I thought “Wow, for centuries this was a mortal sin and now you change the rules. How is that possible?” Pope Francis is very good because he’s humanizing Christianity and saying that as a Christian you should be tolerant of yourself and others.

Rail: You did a series of photographs of members of the clergy in the early ‘90s.

Serrano: It was called “The Church.”

Rail: Did you get any pushback at that time?

Serrano: No. I did that body of work in France, Italy, and Spain. The only thing I got was this: in France I tried to get to the Cardinal of Paris, Cardinal Lustiger. I had to see his assistant and the first thing she said was “Why Piss Christ?” I didn’t tell them about Piss Christ in advance, but of course they look you up. So I explained it. I had a second meeting with her and she said, “You know, Piss Christ is not so much the problem for us as the ejaculation photographs because that’s the sin of onanism.” And then she said, “If you could get another Cardinal first, that would help us.” Something similar happened in Rome, when I wanted to photograph a Cardinal at the Vatican. An Italian friend of mine had given me his name. But she said, “You can’t use my family name.” So this Cardinal in Rome gives me his hand to kiss and he says “Where’s the letter?” I say “What letter?” and he says “The letter of introduction.” And I said “I’m sorry, I don’t have the letter.” And he says, “My son, I can’t do anything without the letter. Bring me the letter and then we can talk.” It’s always about who you know. Even in Rome, you have to know someone.

Rail: But eventually they went ahead with it, right?

Serrano: Not those two, but others yes.

Rail: But you know Jesus! Does that work?

Serrano: In some circles it does.

Rail: What’s next for you?

Serrano: I’ve just made some new work in China. Again, it’s the kind of thing that is obvious to do. I like to go somewhere where I know nothing about the place other than what everybody else knows. Then I find something of interest to me and I blow it up.

Rail: Can you say what you will be doing?

Serrano: I don’t want to talk about it but I can tell you what the show is called: It’s called Made in China.

Rail: What else would it be called? China seems like an interesting place for you to go because there is no Christian tradition there.

Serrano: Actually, there are Christians everywhere!

, 2015. Pigment prints, back-mounted on dibond, wooden frame. 40 x 30 inches each.

Left: Francie McGuigan, Right: Patrick McNally. Courtesy of the artist.">

, 2015. Pigment prints, back-mounted on dibond, wooden frame. 40 x 30 inches each.

Left: Francie McGuigan, Right: Patrick McNally. Courtesy of the artist.">

, 2015. Pigment print, back-mounted on dibond, wooden frame, 60 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist.">

, 2015. Pigment print, back-mounted on dibond, wooden frame, 60 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist.">