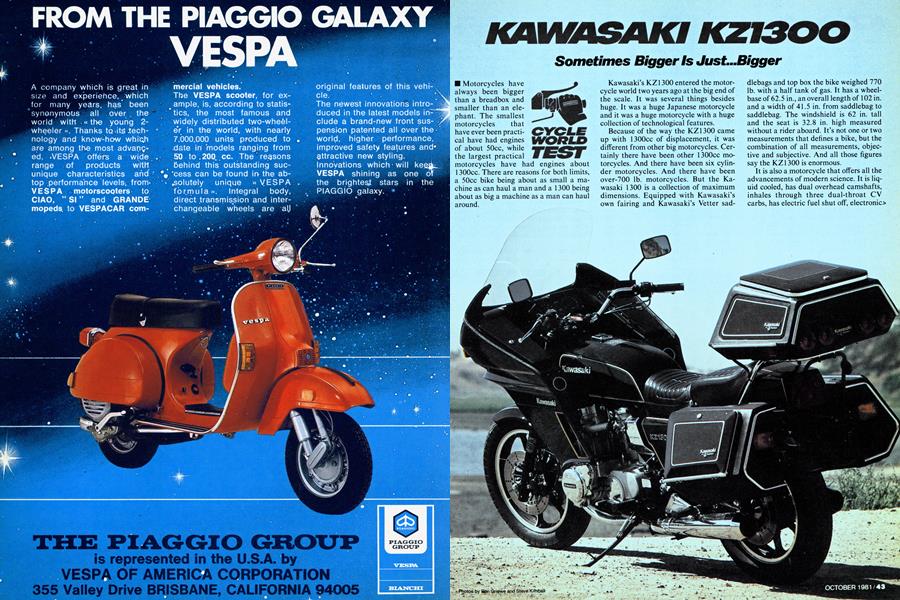

KAWASAKI KZ1300

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Sometimes Bigger Is Just...Bigger

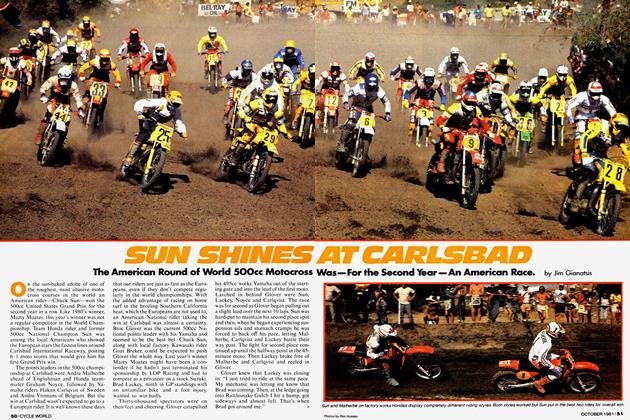

Motorcycles have always been bigger than a breadbox and smaller than an elephant. The smallest motorcycles that have ever been practical have had engines of about 50cc, while the largest practical motorcycles have had engines about 1300cc. There are reasons for both limits, a 50cc bike being about as small a machine as can haul a man and a 1300 being about as big a machine as a man can haul around.

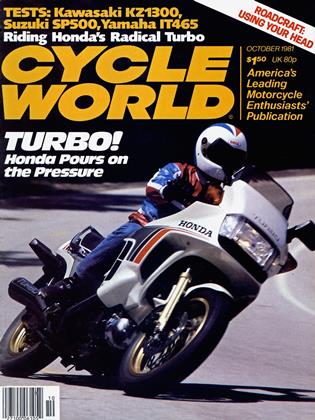

Kawasaki’s KZ1300 entered the motorcycle world two years ago at the big end of the scale. It was several things besides huge. It was a huge Japanese motorcycle and it was a huge motorcycle with a huge collection of technological features.

Because of the way the KZ1300 came up with 1300cc of displacement, it was different from other big motorcycles. Certainly there have been other 1300cc motorcycles. And there have been six cylinder motorcycles. And there have been over-700 lb. motorcycles. But the Kawasaki 1300 is a collection of maximum dimensions. Equipped with Kawasaki’s own fairing and Kawasaki’s Vetter sad-

dlebags and top box the bike weighed 770 lb. with a half tank of gas. It has a wheelbase of 62.5 in., an overall length of 102 in. and a width of 41.5 in. from saddlebag to saddlebag. The windshield is 62 in. tall and the seat is 32.8 in. high measured without a rider aboard. It’s not one or two measurements that defines a bike, but the combination of all measurements, objective and subjective. And all those figures say the KZ1300 is enormous.

It is also a motorcycle that offers all the advancements of modern science. It is liquid cooled, has dual overhead camshafts, inhales through three dual-throat CV carbs, has electric fuel shut off, electronio ignition, air suction emission system, shaft drive, triple disc brakes, air assisted coil spring suspension front and rear, cast wheels, tubeless tires, auxiliary electric shut-off switch, self-cancelling turn signals that can, themselves, be cancelled, four-way emergency flashers, fuel and temperature gauges and thermostatically controlled electric fan.

Kawasaki’s KZl300 has, in short, everything anybody ever asked for on a motorcycle. It’s big, powerful, comfortable, quiet and smooth. Those are the qualities people asked for in a big highway bike and Kawasaki has provided those qualities.

That does not make the KZl 300 a success, however. About the only success for the KZl300 has been success in eluding possession by the American public.

The KZl 300 wasn’t just designed for long distance, it was designed by long distance. It shows all the classic symptoms of a product built for someone else. As long as the people designing the bike won’t be riding it, it doesn’t matter that the seat is high enough and the center of gravity is high enough to make hoisting the machine from the sidestand toan upright position a real challenge.

And it doesn't matter to someone who won’t be riding it that the engine heat is thoroughly trapped by the fairing so that a rider is seared on a hot day.

Being designed by long distance means that the qualities that can be defined analytically are done superbly, while the subjective qualities are what suffer. So the KZl300 is a mechanically stunning motorcycle. The engine is a six cylinder inline, dual overhead camshaft, liquid cooled design with enough chains running around inside it to anchor the Enterprise.

Engine width can be a problem with six cylinders in a row, so much of the KZ1300’s design is an attempt to narrow the engine. The liquid cooling means the cylinders can be spaced closer together. And the engine is undersquare with a 62mm bore and 71mm stroke, again to keep engine width down. By having a single 32mm Hy-Vo chain,drive a jackshaft behind the cylinders, there’s only one sprocket on the crank. From the jackshaft a 40mm silent-type chain drives the clutch. The camchain and an auxiliary shaft drivechain both are driven by the jackshaft. The auxiliary shaft operates the ignition and drives another driveshaft which operates the waterpump. While the mechanical paths of power on the KZl 300 are unusual, the rest of the engine is not. At least not in 1981. The dual camshafts operate the valves through shims, just like the system used on other Kawasaki multis. The air suction emission system on the 1300 is just like that on other Kawasakis, too. There are just two valves per cylinder, the alternator is on the righthand end of the crankshaft, the rubber-damped clutch is very much like other Kawasaki clutches and the five-speed transmission has a 2nd gear lockout for easy neutral finding.

Being like other Kawasakis, the 1300 naturally has lots of horsepower for its size and that horsepower is spread over a wide range of engine speeds. In the 1300’s case the redline is 8000 rpm where the engine is putting out something like 120 horsepower. Even at low revs the engine is powerful. Running down the road in high gear at 3500 rpm the rider doesn’t need to downshift for hills or passing unless he wants to leave his Honda-riding friends behind. A natural byproduct of cubic inches (or ccs) is torque. Having lots of displacement, the Kawasaki has lots of torque.

If there is a problem with the engine’s power delivery it’s that the engine combines massive power with minimum flywheel effect and too-sudden carb response. It’s not as easy to get underway on the Kawasaki as it is with other big bikes because the engine can die if the clutch is released while the engine is spinning at under 2000 rpm. It can’t be lugged at idle like a GS1100, for instance. So first-time riders kill the engine a time or two getting started. Then they grab a handful and sometimes get more than they want. The CV carbs are wonderful at providing quick throttle response, but for ease of riding, the response can be too quick.

Where the 1300 departs from normal practice is in the design of ancillary pieces. Printed circuits enable the electric fan motor to be shaped flat like a pancake. Combined with the thermostat and aluminum radiator, engine temperature will normally vary greatly, running right up to the maximum limits on the temperature gauge in city traffic before the fan comes on and cools the engine.

Controls on the 1300 aren’t standard Kawasaki. The lefthand control pod uses a rotating collar for headlight beam, there’s a rocker switch for four-way flashers and inboard of the flasher switch is another rocker switch to turn on or off the selfcanceling turn signals. The actual turn signal switch is below that and below the turn signal switch is a horn switch. That control pod is a small-scale example of how the 1300 works. Every possible switch is located there. All the switches work just as they’re supposed to. Yet the entire pod is so large because of all the switches that it’s difficult to reach some of the switches and the controls never become easy to use. The rider continually has to think that the parallel rocker switches should be switched in opposite directions for normal use and whenever the self-canceler is shut off, the flasher switch is usually turned on too, because it’s too close to the other switch.

One of the few changes made to the 1300 since its introduction has been to the suspension. The original 1 300 would bottom the rear suspension anytime two people rode the bike on anything rougher than a pool table. Now there are air assisted springs in the rear and the damping can be set to any of four positions. On minimum air pressure and damping the ride is soft and pleasant for one rider and still superior to the previous suspension for two-up use. For most two-up or fully loaded riding the pressure can be pumped up to 70 psi and the damping set to maximum. The ride is still pleasantly comfortable and supple, but it’s also controlled and doesn’t bottom. The interconnecting line makes filling the suspension units much easier and keeps pressure equal on both sides, a useful feature.

Suspension in front is the same massive air assisted forks. A single filler cap is used, now with a crossover tube linking the two fork legs. Spring rate is sufficient for the loads on the bike while comfort isn’t sacrificed. Considering the 770 lb. weight of the dressed Kawasaki, the sus-

pension does an admirable job of supporting the weight, providing a comfortable ride and enabling the machine to go around corners.

Keeping the wheels lined up and the suspension tied together is one of the more massive frames ever used on a motorcycle. It’s a double downtube full cradle type frame, using giant double wall downtubes and beefy cast junctions at the swing arm pivot. Other cast pieces are used at the end of the swing arm opposite the driveshaft housing. The frame is solid, doesn’t appear to flex and enables the Kawasaki to carry a heavy load. It also is big.

To make room for six big cylinders and all the other parts that must be sized accordingly the frame is long and tall and wide. That’s why it has a 62.5 in. wheelbase and why the seat is nearly 33 in. off the ground. More than just the physical size, the KZ1300 has its weight spread around the motorcycle and much of it up high. So when the machine is leaned onto its sidestand, even on flat pavement, it takes a lot of muscle to straighten up the bike.

That’s only the start of the mega-muscle routine required of the KZ1300 rider. The throttle return spring is excessively stiff, even for the three double-throat CV Mikuni carbs. And the clutch pull is firm, adding to the sensation that this motorcycle is being wrestled, not ridden.

What all the physical effort provides is for this huge motorcycle to go down the road, aimed at something, waiting for the rider to try and turn it. Yes, it can be turned. It can go around corners at a moderate pace and it doesn’t wobble or have a severe cornering clearance problem. The challenge of turning the 1300 is in giving it enough effort to get it heeled over, but then put enough pressure in the opposite direction to keep it from falling over. This is not one of those motorcycles that knows its own way around corners. It requires effort and concentration from the rider for any cornering.

In exchange for clumsy cornering and stiff controls, the KZ1300 provides stability. It will go straight down any road oblivious to crosswinds, trucks, road surface or wingtip vortices. When it’s going straight down a highway it rides pleasantly and the layout of the machine is reasonably comfortable. The seat is not plush. It’s a bit firm, but the shape is acceptable. The handlebars are an excellent bend for a touring bike equipped with a fairing. They come back just far enough without forcing a rider to lean back. The bend puts wrists at ease and helps the seat do its job. Even pegs and controls are convenient to reach. There is a noticeable amount of vibration that comes through the handlebars and other parts of the motorcycle. That vibration blurs the images in the mirrors and buzzes the riders. It combines with a booming resonance in the exhaust so that the 1300 is not a restful motorcycle to ride over long distances.

Braking performance of the 1300 is acceptable, but not comfortable. Use the front brakes hard and they produce some strange noises and generally indicate their dislike for such exercise. The front brakes also require a substantial effort for maximum braking pressure. Combined with the ponderous weight of the motorcycle, the brakes don’t encourage hard use, though they seem able to handle it.

Because this is a motorcycle for highway use, Kawasaki offers a full package of accessories. The fairing is Kawasaki’s own design, big enough to wrap around the wide gas tank. It’s also wide, tall and has spacious cargo room beneath the locking plastic covers. Since it was first produced the Kawasaki fairing has grown a pair of small air vents by the rider’s knees. They are there for good reason, but poor effect.

This is of special importance on the Kawasaki 1300 because of the great quantity of heat that is emitted from the radiator. When riding the bike on even a cool day there’s a blast of hot air running onto the rider’s legs. On a warm day that blast of hot air is enough to cause fatigue and make riding uncomfortable for even short distances. On a hot day the bike becomes unbearable. After a ride across town on the Kawasaki a rider can feel as if he’s done a half hour of calesthenics in a steam room.

Other accessories on the 1300 are made by Vetter. The two saddlebags and the top box are standard issue Vetter pieces with the name Kawasaki by Vetter on the luggage. As such the quality is very good and all the storage bins are large and relatively easy to use. There are some nuisances, however. The top box is not a quick release type, which would be preferable. Also, the lid to the box is held upright by a spring which is too short, forcing a rider to use one hand to hold up the lid while he packs the box. An inch-longer spring would allow the lid to hold itself up for loading. The saddlebags can be easily loaded when on the bike because of the angled design, but that same design creates excessive width on the massive Kawasaki. A solo bike that’s 42 in. wide from side to side becomes difficult to maneuver at times.

When a rider assembles a collection of accessories on a motorcycle he normally ends up with a pocket full of keys to operate all the different pieces. When a factory assembles all those parts there’s no excuse for not using one key for everything. The Kawasaki has four keys. The ignition key only operates ignition, the auxiliary ignition switch and a helmet lock. A second key opens the covers on the fairing storage pockets. A third key unlocks the top box and a fourth key unlocks and can disconnect the saddlebags.

Since the 1300 was introduced in 1979 it has been changed slightly. Besides the new rear suspension this year, the bike has undergone a minor restyling. The angular 5.6 gal. gas tank has been replaced by a more conventionally styled 5.4 gal. gas tank. The addition of gold pinstriping on the new black paint makes the 1300 appear smaller than it did. Chrome plating has been added to engine side covers and air filter side covers.

Most of the changes on the 1300 are small; even insignificant. The rearview mirrors are now tinted. Handgrip rubber is softer, though they don’t feel particularly different. There’s a passenger grab rail behind the seat. Two helmet locks are provided. An auxiliary electrical terminal is provided.

One change that isn’t for the better is the addition of the positive neutral finder. This prevents the bike from being shifted from neutral to 2nd. This also means that if the battery is low or the bike won’t start at high elevation it can’t be push started. That’s not a good idea.

While the Kawasaki 1300 suffers from a few irritating bad ideas, it does have an excellent collection of good ideas. It’s a mechanically sound bike, with incredible horsepower and torque. The rest of the drivetrain seems more than able to handle the power, with any easy shifting transmission and drive shaft that has very little slop and excellent manners under all conditions. The suspension shows a proper combination of spring and damping rates, plus it has air adjustability, equalizing tubes for the air pressure both front and rear and the rear damping is easily adjustable without tools.

If the bike’s accessories were less of a burden on the Kawasaki its inherent good points would make it an exciting motorcycle. And certainly some of the competition benefits from well thought out, carefully designed accessories that add to their motorcycles’ good points.

As it is, Kawasaki’s biggest touring bike is a sound machine that offers not quite as much comfort and ease of handling as other big bikes and provides a bit more horsepower in compensation.

In its present configuration, the KZ1300 demonstrates why bigger motorcycles haven’t been successful. There is a practical limit of weight and power and the 1300 is very close to that limit. For most riders it’s just a little over the edge.H

KAWASAKI KZ1300

$6260

View Full Issue

View Full Issue