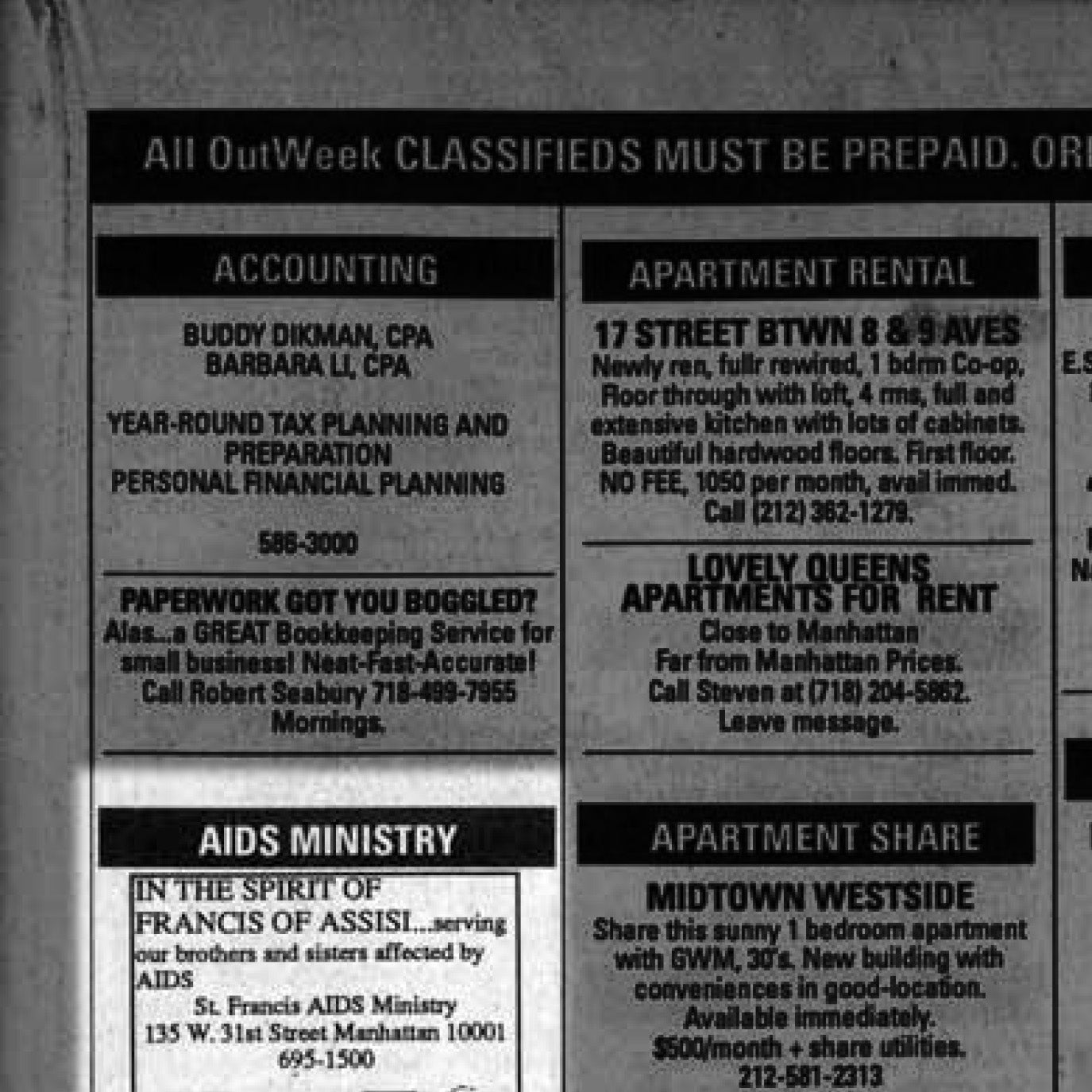

When Salvatore Sapienza saw the small classified ad in the back of OutWeek, a gay news magazine in New York, he thought it seemed like a sign. “In the spirit of Francis of Assisi,” the ad read, “serving our brothers and sisters affected by AIDS.” At the bottom was the address of the St. Francis AIDS Ministry on West 31st Street in Manhattan. Sapienza was gay—he had been out for years—but he was also a Marist Brother, a Catholic office similar to the priesthood. New York City in 1989 was not an easy place to be both gay and Catholic. The AIDS crisis would claim more than 5,000 people in the city that year, and the church was vocally opposed to condoms and homosexuality. Sapienza felt like that little bulletin, appearing among pages advertising sex phone lines and astrologists, was written just for him. A black-and-white drawing showed the 13th-century saint, a symbol of charity and humility, overlooking a pastoral landscape as skyscrapers loomed in the background. Sapienza found himself wondering who’d placed the ad.

The address for the St. Francis AIDS Ministry turned out to be the Church of St. Francis of Assisi. Four people answered the ad, including Sapienza, and soon they were visiting AIDS patients in hospital rooms, praying for them and holding their hands. When Sapienza first showed up at the soaring 19th-century church, he was led inside to a tiny office on the ground floor of the attached friary. The beaming man who greeted him seemed big in every way: tall, loud, boisterous, and joyful. His name was Father Mychal Judge.

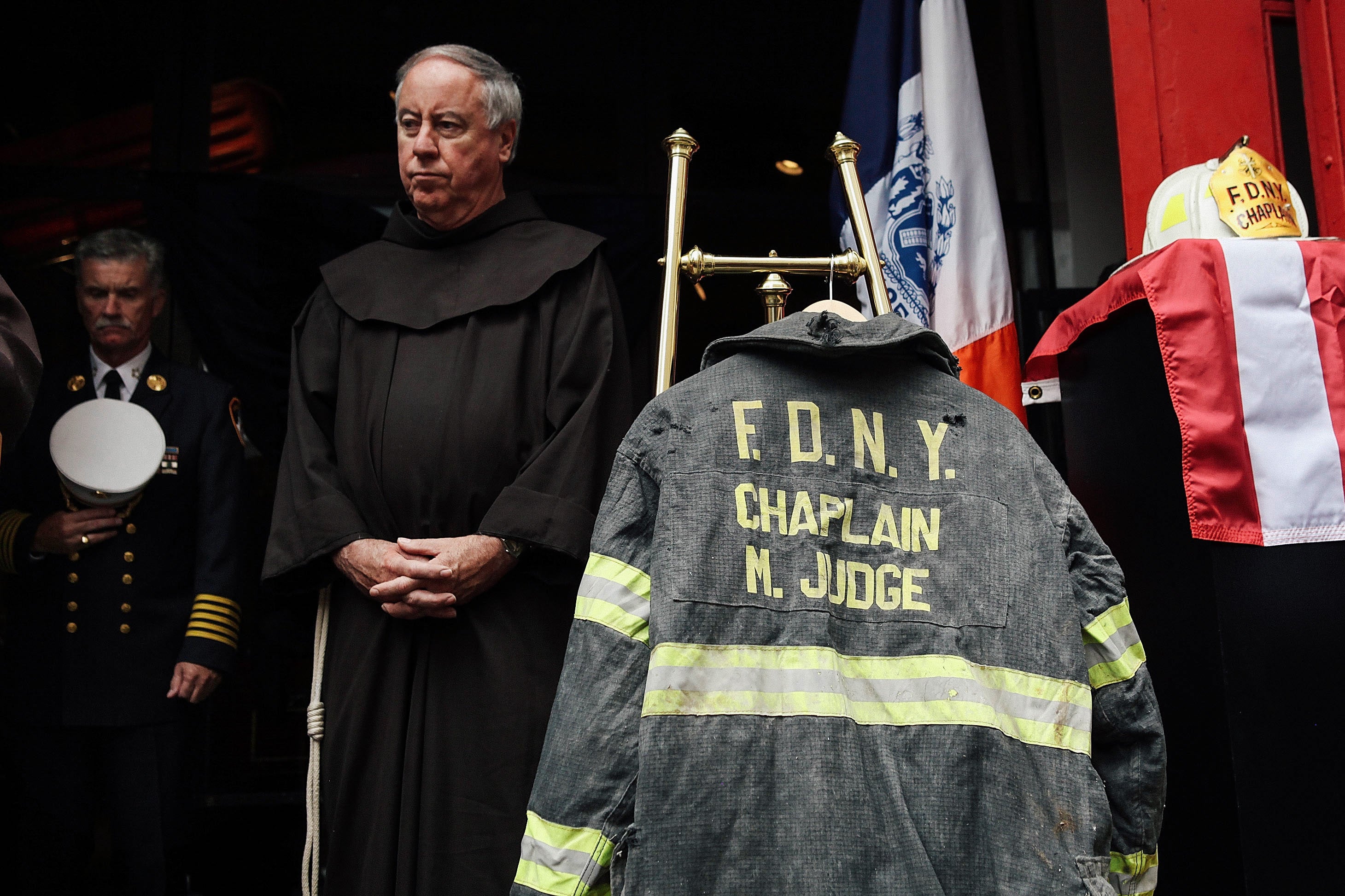

Nearly three decades later, Judge is best known as the fire department chaplain who died on Sept. 11, 2001, after rushing into the north tower of the World Trade Center to help. His life quickly took on an almost mythic stature. A documentary crew’s camera found him praying in the lobby of the north tower, wearing a white helmet reading “F.D.N.Y. Chaplain.” (Firefighters would later present the helmet to Pope John Paul II.) A story spread that he had died not just in the north tower but while administering the last rites to a firefighter who was hit by a jumper. A striking Reuters photo of first responders carrying Judge’s body out of the dust has been referred to as a “modern Pietà” and has been turned into sculptures in crystal and bronze. By 2002, New York City had renamed his stretch of West 31st Street “Father Mychal F. Judge Street” and christened a public ferry the Father Mychal Judge. In New York, hundreds of firefighters and others participate each September in a Stations of the Cross–style procession that retraces Judge’s journey between the Church of St. Francis on West 31st Street and the World Trade Center. Speaking at Judge’s funeral on Sept. 15, 2001, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani said simply: “He was a saint.”

But to Sapienza, Judge is deserving of that honorific for reasons that are less widely known. At a time when some doctors were still afraid to touch or even treat AIDS patients, Judge cradled dying men in his arms, administered the Eucharist and the last rites, spoke at their funerals, and comforted their families and friends. “Mychal really knew that gay Catholics were being treated like second-class citizens by the church,” Sapienza said. Judge “loved being Catholic,” Sapienza said. But he also “loved being gay.”

Being a saint in the colloquial sense—a mensch, a hero, a faithful Christian—is one thing. Becoming a Catholic saint, formally recognized by the Vatican, is another: a long, expensive, and politically fraught process that involves a lengthy investigation and proof of literal miracles. There are two broad categories of saints: “martyrs,” who died specifically for their faith, and “confessors,” who demonstrated a lifetime of what the church defines as “heroic virtue.” Historically, the entirety of a person’s life was subject to strict scrutiny on the path to canonization.

But in July, the Vatican announced that it had expanded its criteria for sainthood, creating a new category for people who willingly sacrifice their lives for others: oblatio vitae, the “offering of life.” This new category of saints does not need to have been killed directly because of their faith, and they need display only “ordinary” virtue. As Mathew Schmalz, a religious studies professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts, put it, “Now saints can be persons who lead a fairly ordinary life until an extraordinary moment of supreme self-sacrifice.” It’s a category that seemed custom-built for Judge.

It was the Rev. Luis Escalante, an Argentinian priest living in Rome who’d never met Judge, who pushed the idea of Judge’s canonization just weeks after the new criteria were announced. Escalante works part time as an independent “postulator,” a role something like a lawyer who represents a potential saint’s candidacy. He decided to start gathering stories and documents from people in America who knew Judge—the first step toward establishing his fitness for canonization. Escalante told me that he thought of Judge’s story as soon as he heard about the new category, in part because his death was such a moving example of Christian self-sacrifice in the midst of violence—an illustration of the idea that “only God can produce sanctity in a terrorist attack.”

Sapienza and others who knew Judge describe him as a man of almost supernatural charisma, an extrovert who enveloped everyone he met into his aura. But few in the wide circle who adored him and relied on him were aware during his lifetime that he was gay. “I was one of Mychal’s 9,412 best friends,” said Michael Daly, a former New York Daily News columnist who wrote a 2008 biography of Judge, The Book of Mychal. “And 9,406 of us didn’t know he was gay.” After Judge died, some whom he had confided in began to speak openly about it, including Thomas Von Essen, the city’s fire commissioner during the Giuliani years. Daly, who had access to Judge’s diaries, reported in his book that Judge had written about being gay and had a long-term romantic relationship with a nurse named Al Alvarado who was 30 years his junior. Sapienza, too, wrote a book that frankly discussed the priest’s sexuality.

On paper, Judge’s sexual orientation should be no barrier to official sainthood. There’s no known evidence that Judge ever broke the vows of chastity that he took in the late 1950s. “Even to traditionalist Catholics, he should be perfectly acceptable because he lived what the catechism taught,” said James Martin, a priest and editor-at-large of the Jesuit magazine America. When it comes to the prospect of canonizing the first gay saint, Martin said, “Mychal Judge is a perfect test case.”

But just because Judge seems to fit perfectly the expanded definition of sainthood does not mean he is destined for the canon. A saint is not just someone who has ticked off certain boxes of Catholic virtue. He is also someone who, in the words of Pope Francis, as he canonized two former popes in 2014, “gives direction and growth to the Church”—a church that, in 2017, still regards homosexuality as “objectively disordered.” In Judge’s embrace of his own sexuality—even if it was a celibate embrace—he presents an implicit challenge to Catholic orthodoxy. Sixteen years after Mychal Judge’s death, what would it mean for the Catholic Church to elevate an LGBTQ person to sainthood and all the honors that come with it?

Throughout his life, Judge had a complicated relationship with the Catholic Church. He sometimes gave Communion to non-Catholics; he abridged requirements for things like premarital counseling and training of lay ministers; he strayed from standard prayers while celebrating Mass; and at least once he discouraged a willing convert from abandoning her Judaism. For a man known for his selflessness and decency, he could be prickly when it came to the church hierarchy, whom he referred to as BFMs, or big fat monsignors. He once wrote to a fellow friar, “I often feel I’m in a different church than them.” He had a particularly contentious relationship with Cardinal John O’Connor, who served as archbishop of New York during almost all of Judge’s years in the city. In Daly’s account, O’Connor, a more conservative, rule-bound Catholic, bristled at Judge’s popularity among both politicians and firefighters’ families. “Did you ever see Amadeus?” Daly asked. “Mychal was Mozart. Cardinal O’Connor wanted to be a great priest, but he didn’t have it. Mychal just had it.”

Judge started training to become a priest at age 15, choosing to join the Franciscans, an order known for their simple lifestyle and ministry to the poor. The new priest spent most of the early years of his career serving parishes in New Jersey, before being assigned in 1986 to St. Francis of Assisi Church in Manhattan. He lived at the church’s friary for the rest of his life. He was not a diocesan priest, the kind who celebrates Mass at Sunday morning services. St. Francis of Assisi is a “service church,” open to commuters and confessors but without its own parishioners. Instead, Judge worked with the homeless, the hungry, and addicts. When the Archdiocese of New York banned a Manhattan church from offering a regular special Mass to a gay Catholic group, Dignity, Judge invited the group to operate out of St. Francis of Assisi Church—one of the perks of operating outside diocesan control.

In the early 1990s, he became a chaplain for the fire department, an agency historically dominated by Catholics. The job demanded that he rush around the city when fire broke out and comfort firefighters and their families afterward in burn units. Long after the Catholic Church released priests and nuns from the obligation to wear formal habits that set them apart, Judge continued to wear the traditional brown hooded robe and rope belt of the Franciscans. “This is my uniform,” he told Sapienza, who preferred to think of himself as too hip for the habit. “People know to come to a police officer or a firefighter for help. People know to come to me for help.”

Judge ministered to populations who often did not feel particularly warm toward each other. In 1993, he marched in both the St. Patrick’s Day Parade—whose organizers were then engaged in a legal battle to prevent gay groups from marching—and the Pride Parade, which proceeded down Fifth Avenue in the opposite direction. There’s no evidence that Judge broke the vow of celibacy he made when he entered the priesthood, despite his close, decadelong relationship with Alvarado.

In 1999, Judge wrote in his diary about how he struggled as a gay man.

“No one, absolutely no one lives two fuller separate lives than I do,” he wrote, before veering back toward his bedrock optimism. “Well, I am so blessed and my life is so good. … Thank you Lord for all that you have given me, for all you have taken away and for all that is left.”

On the morning of Sept. 11, a fellow priest who had witnessed the plane fly into the north tower rushed to tell Judge the news. He immediately put on his collar and drove downtown with an off-duty captain and a firefighter. As he knelt in the north tower’s lobby, firefighters streamed to stairways, and bodies crashed down as office workers jumped from higher floors. “You should go, padre,” one firefighter told him. “I’m not finished,” he replied. He was somewhere near the north tower’s blown-out windows when the south tower collapsed at 9:59 a.m. When the dust cleared, firefighters stumbled over his body as they began to evacuate. Four men picked him up, later joined by other first responders as they carried the body outside and along Vesey Street. Eventually his body arrived at the chief medical examiner’s office, where a clerk numbered his death certificate “DM0001-01.” The “DM” stood for “Disaster Manhattan”: Judge, 68, was the attack’s first official victim. At his funeral, when St. Francis of Assisi overflowed with mourners, Alvarado was not allowed inside because no one knew who he was.

In some ways, the time now feels right for Judge’s canonization. While Pope Francis has made no dramatic moves to dismantle Catholic orthodoxy regarding homosexuality, he is widely perceived as having taken a gentler tone than his predecessors. “Who am I to judge?” he famously asked in 2013, answering a reporter’s question about gay priests; he later expanded on the comment, explaining that he applied it to all gay people. “There’s a real opening under Francis, but the door will only remain open for so long,” Schmalz said. “If you’re going to push things publicly, now’s the time to do it.”

Within a week of the Vatican’s announcement about the new sainthood criteria, Escalante reached out to Francis DeBernardo, an American and longtime activist on behalf of gay Catholics, and asked him to help find people who knew Judge. “For the sake of this heroic priest who literally gave his life for others,” DeBernardo wrote on his organization’s website, “please spread the word!” Escalante has heard from about 40 people so far. “That’s a sign that he has devotion,” he said. “There is a reputation for sanctity.”

There are currently at least 10,000 Catholic saints, but the exact number is squishy. Until around the year 1000, local bishops named their own saints without much oversight. Those “saints” include folk heroes like St. Christopher, who may never have actually existed; in one case, a rural French community venerated a dog. As the papacy consolidated its power, canonization become more orderly—and baroque. Today, the process involves a detailed investigation of candidates’ lives, including examination of their writings to see if they are consistent with Catholic doctrine. If the pope then declares the candidate “venerable,” the person must be found responsible for a miracle occurring after that point, typically a healing investigated by a nine-member medical board.

Pope Francis has canonized 838 people—the most of any pope by far—but about 800 of them were a single group of 15th-century martyrs. The full process can take centuries, though newer cases often move more quickly. After his death, Pope John Paul II went through the full process in nine years, which was the most expeditious canonization in history.

Escalante will ultimately need the support of Judge’s group of Franciscan friars in New York; he has not heard from them, and he acknowledges that Judge could be a “challenging candidate,” in part because of his conflicts with local church authorities. A representative for the group confirmed to me they are not working on his “cause,” a position they have maintained since his death: “Father Mychal would be glad people are interested in the work he did, but he wouldn’t have wanted to be singled out in any way.” Then again, surely the Catholic Church shouldn’t be too eager to nominate a saint who was desperate for sainthood. The explanation that “he wouldn’t have wanted to be singled out,” Schmalz told me, “doesn’t pass the smell test.” “I think they’re worried about the sexuality issue and potential conservative Catholic responses,” he said.

As of now, there are no Catholic saints who are known to be gay. But Mychal Judge would not be the first saint who could be described plausibly as LGBTQ. There’s Joan of Arc, who dressed as a male soldier to do battle in the Hundred Years’ War, and the early martyrs Sergius and Bacchus, who some historians say had a romantic relationship. The 19th-century British Cardinal John Henry Newman, beatified in 2010, left explicit instructions that he was to be buried in the same grave as his lifelong companion, a fellow priest. (As Newman progressed toward sainthood, the church ordered his body exhumed, purportedly to move him to a more accessible location. It had disintegrated too much to move.) The hints of queerness in their stories are cherished by some Catholics and hotly debated by others. “The sad thing is when you bring this up, it’s as if you’re casting aspersions,” said Martin, the author of a recent book on the relationship between the church and the LGBTQ community. “It’s not an insult to a saint to say he or she was attracted to the same sex and still lived celibately or chastely. Why can’t an LGBT person be considered holy?” But the question for the Catholic Church is not whether an LGBTQ person could be considered holy in a general sense. It’s whether Catholicism is ready for a saint whose sexuality could not be ignored or dismissed as a matter of historical interpretation—a modern gay man who, as Sapienza put it, loved being gay and loved being Catholic.

Although American Catholics as a group are relatively progressive on sexuality issues, the growing church in the global South is much less accepting. The issue is fraught for the church hierarchy, too. Even as Pope Francis has hinted at a new relatively laissez-faire approach, the Vatican confirmed last year that “persons with homosexual tendencies” should not be admitted to train as priests at Catholic seminaries. For now, most consider Judge a long shot for sainthood, in part because his religious order has so far declined to take up his cause. “I would pray for his canonization but I wouldn’t bet on it,” Schmalz said. “If you look at the church worldwide and church hierarchy, [Judge’s canonization] would be incredibly problematic,” he explained. “It’s a kind of litmus test as to how deep the culture wars in Catholicism go, and whether they can be transcended.”

For gay Catholics, the results of that litmus test matter. Judge’s canonization “would be a much clearer statement that you have a place in the church, and the church doesn’t judge you by your temptations but by living a life of obedience,” said Ron Belgau, a celibate gay Catholic who has urged the Vatican to be more welcoming to LGBTQ people. “Even to those who disagree with church teaching, it would help to change the idea that there’s no place for them in the church, that they’re outsiders.” In a way, canonizing Judge—who obeyed the rules, even as he chafed at them—would be a deferral of more difficult questions about how the Catholic Church deals with LGBTQ people. “Oftentimes when someone is canonized, all the rough edges are sanded down,” said Martin. “Would the Franciscans allow him to be known as a gay man? That’s the question. We tend to tame the saints.”

In 1999, Judge contemplated in his diary whether he could come out someday by writing a book. “Every group can have an advocate,” he wrote. “Maybe, maybe a chapter in a book by Mychal Judge—well respected, loved by many, faithful to his profession, loyal to his community and friends … well if he is gay there must be something okay about ‘them.’ ” Judge never got around to writing that book. Maybe he was afraid to, or maybe he simply ran out of time.

A decade before Mychal Judge knelt in the lobby of the north tower, Sal Sapienza left the Catholic Church. Today, he is married and works as the pastor of a Protestant church in Michigan. Even if Judge is never elevated to sainthood, Sapienza says, his legacy is hard to overestimate. But what appeals to Sapienza most about the prospect of canonization is that it would “bring Mychal to millions more people.” “As a young idealistic person, I thought I could be this bridge between the gay community and the Catholic community,” he said. “Mychal worked to the end of his life to be that bridge.”

Top image: Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo of Father Mychal Judge by Jim Lord/Getty Images, background via Met Museum.