Milan, 14 June 2020

Revised in Vienna, 20 October 2020

In the recent hikes which my wife and I have been doing, we’ve come across a lot of these.

“These” are woodland strawberries (but see the Postscript at the end). I throw in here a much more professional photo of this plant, to give readers a better view.

The fact is, though, that they are really very small, no more than half a centimetre across, as this photo of a whole sheet of them shows: they are just bright red dots against the green of the leaves.

Those bright red dots always catch my eye as we walk along. From time to time, I’ve picked one of the bigger ones and eaten it. They are pretty bland, I have to say. Their taste is really nothing to write home (or a post) about.

Which – as I tramped along – got me thinking: who were the people who laboured so hard to turn these small, not very tasty berries into the big, juicy and wonderfully sweet berries that we eat today?

Readers of my posts will know that I have a fondness of saluting the almost always anonymous folk who over the millennia have coaxed tasty foodstuffs which we eat today out of small and not so tasty wild plants. The last such foodstuff whose creation I have saluted is the common chicory. I decided to do the same thing for the strawberry. And so I have been beavering away on my computer these last few weeks, surfing the web and seeing what I could find.

The first thing I found was that I had been completely wrong. Today’s strawberries do not descend from those little woodland strawberries we had been spotting on our walks. They are not the result of countless generations of rural people patiently selecting woodland strawberry plants with ever sweeter and ever bigger fruits. The story of today’s plump and juicy strawberries is much more complex. They are actually the result of Europe having colonised much of the rest of the planet.

But let me start where all good stories start, at the beginning. It is true that Europeans had at one time domesticated woodland strawberries. Perhaps the Romans had done so, but if they did these domesticates were lost during the Dark Ages. Medieval Europeans certainly started domesticating them. King Charles V of France, for instance, has his gardeners transplant 1,200 woodland strawberry plants into his gardens some time in the late 1300s. Europeans also started domesticating the other species of strawberries which are found in Europe, the musk, or hautbois, strawberry, which is somewhat bigger than the woodland strawberry

and the creamy strawberry, which as its name suggests can be quite pale; it’s about the same size as the woodland strawberry.

It’s hard to tell from surviving documents, but Medieval and Renaissance gardeners do seem to have created strains of strawberries which were bigger and sweeter than their wild cousins. But by “bigger” I mean something as big as a plump blackberry, no more than that.

Then started the period of European colonisation. In the Americas this led to, among other things, the transfer of a wealth of new foodstuffs to Europe, a phenomenon I’ve touched upon in a couple of past posts. Maize, tomato, and potato are probably the most well known of these arrivals from the Americas. Like these three, most of the new foodstuffs came from Central and South America, but a few also made their way from North America. The best known of these is the sunflower, while I recently wrote a post about another, more modest transfer from North America, the Jerusalem artichoke. And now I have discovered that there was yet another transfer from North America: the Virginian (or scarlet) strawberry! This species of strawberry grows throughout much of North America, but it was of course first seen by Europeans in the colonies strung along the eastern seaboard.

These colonists must have been quite pleased to have this new strawberry plant at hand. We’re still not talking of berries the size of those we’re now used to – its berries were about the same size as those of the European musk strawberry. But no doubt they would have seen them as a useful adjunct to their diet.

When exactly someone brought plants of the Virginia strawberry back to Europe is not clear – the early 1600s seem to be the most probable time frame. And what country they brought them back to is not clear either – the British, French and Dutch all had colonies in the strawberry’s range, so any of these three countries could have been the original entry point, and maybe the plant was introduced into Europe more than once. Wherever its entry point (or points) was, the Virginia strawberry didn’t spread that quickly through the rest of Europe. It seems to have been more of a curiosity, and certainly didn’t replace the European species with which people were familiar.

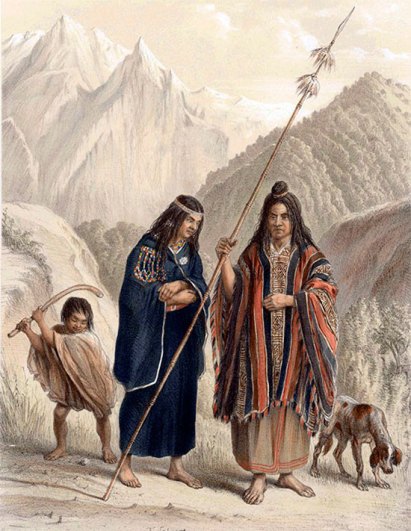

While the French, British, and Dutch were busy colonising North America, the Spaniards were busy colonising Central and South America. In South America, they first smashed the Inca Empire. Then they turned their attention further southward. It made strategic sense for them to control the whole of the Pacific seaboard down to the Straits of Magellan, to keep an eye on other pesky European nations coming through those straits for who knows what nefarious reasons. So they went on to conquer what is now Chile. In the south of Chile, the Spaniards encountered the Mapuche and Huilliche peoples, who put up a stiff resistance but who were eventually overcome and subjugated.

The Spaniards discovered that these two tribes had domesticated another local species of strawberry, the Chilean (or beach) strawberry. And in this case the berry was pretty damned big!

The Spanish colonists were very happy to add the Chilean strawberry to their local diet, to the point that it was commonly available in local markets in the new Spanish towns of southern Chile. It remained, however, a local delicacy. If anyone ever tried to bring back plants to Spain, there is no sign of them having succeeded.

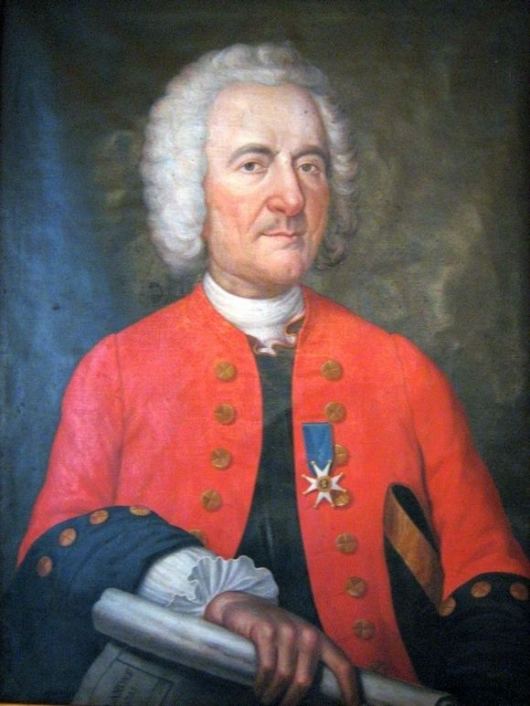

So things stood until 1712. In that year, King Louis XIV of France sent a certain Amédée François Frézier on a secret mission to Chile. We have here a portrait of Frézier in old age, after a long and successful career.

His orders were to find out all he could about the Spanish military presence there: forts, harbours, military units, and so on (this was part of Louis XIV’s ongoing struggles with Spain). For nearly two years, Frézier followed his orders most diligently, posing as a merchant looking for trading opportunities. But Frézier was a man of many interests, one of these being botany. Naturally enough, the Chilean strawberry, with its very big fruit, caught his attention. As he was to write later:

They there cultivate entire fields of a type of strawberry differing from ours by their rounder leaves, being fleshier and having strong runners. Its fruit are usually as large as a whole walnut, and sometimes as a small egg. They are of a whitish-red colour and a little less delicate to the taste than our woodland strawberries.

Frézier determined to bring some plants back with him when he returned to France. So it was that when in 1714 he finally boarded the ship which would be taking him home, he took five plants of the Chilean strawberry with him, and managed to keep alive on the long – and hot – trip home. When he arrived in France, he kept one of the plants for himself and sent the others to various friends and patrons. News of this new species of strawberry quickly made the rounds among Europe’s little circle of amateur botanists, especially after Frézier’s book was published in which he gave a detailed account of his doings in Chile and included a description of this strawberry plant with such large fruits. Strawberry plants are easy to propagate, so not only did news about the Chilean strawberry get around; so did clones of the various plants he brought back. Anyone with a serious botanical garden had to have the plant in their collection!

Alas! Great disappointment lay in store for many of those eminent botanists who planted the Chilean strawberry in their garden and eagerly awaited it to flower and – especially – to fruit (“usually as large as a whole walnut, and sometimes as a small egg”, Frézier had written). For the most part, their plants yielded nothing – nada, zero! They began to think that maybe the plant’s transfer to Europe had made it sterile.

Here, with the advantage of hindsight, I shall cut through all the intellectual confusion that pervaded the minds of Europe’s finest botanists for several decades. The fundamental problem was this: they hadn’t realized that some species of plants are hermaphrodites, and so can self pollinate, while in other species there are separate male and female plants, so both have to be present – and relatively close to each other – for pollination to occur. It just so happens that all the European species of strawberries are hermaphrodites, as is the Virginian strawberry, but the Chilean strawberry is not. There are both male and female plants in that species. Frézier must have taken only plants which were fruiting, and therefore females. This was sensible enough, given his (and everyone else’s) knowledge of strawberries; he wanted to be sure that the plants he nicked were fertile. But what this meant is that there was no way that those poor female Chilean strawberry plants, along with their clones which all the botanists were busy sending each other, were ever going to fruit in Europe without a male plant handy. This mystery was finally elucidated in the early 1760s by a young Frenchman called Antoine Nicolas Duchesne, who had a fascination for natural history. He was lucky to have access to King Louis XV’s gardens at Versailles and to be mentored by the “Assistant Demonstrator of the Exterior of Plants at the King’s Garden”, Bernard de Jussieu. After making a detailed study of strawberries, he explained all in his book Histoire naturelle des fraisiers published in 1766, when he was a mere 19 years old! Here is picture of him in old age.

But actually there was a way to make the Chilean strawberry produce berries! The discovery had been made some time in the first half of the 1700s by those anonymous farmers whom I love to salute. While all those well-off, educated botanists were tearing their hair out at the Chilean strawberry’s obdurate refusal to fruit, they had found a way to coax it to do so – by interplanting the plants with either Virginian strawberry plants or musk strawberry plants. The pollens of these species were closely related enough to that of the Chilean strawberry to pollinate it. Presumably, by chance a farmer (or his wife) had planted these various species close together in their strawberry patch, had seen that the Chilean strawberry fruited under these conditions, and were sharp enough to draw the right conclusion. Who exactly these clever farmers were will of course never be known. But the chances are that it was one or more farmers from around the French city of Brest, in Brittany (Frézier was posted to Brittany on his return from Chile, which probably explains this Breton connection), although it could (also) have been farmers in the Netherlands.

And what fruits they were! Big, juicy, sweet – everything that Frézier had said of the strawberries he had eaten in Chile. Further experimentation showed that the two species from the Americas, the Virginian strawberry and the Chilean strawberry, gave birth to a fertile hybrid, which could be grown as a separate species. On top of this, this hybrid was hermaphroditic so no need for all that fiddly stuff of making sure to plant males and females together! This hybrid is the garden strawberry, the modern strawberry eaten all around the world today.

An industry was created, which currently produces some 9 million tonnes of garden strawberries per year, (with – sign of the times – 40% of that being in China).

And what of the strawberries which this hunking hybrid of a strawberry displaced? The woodland strawberry has disappeared back into the woods from whence it came and where I found it at the beginning of this post. As far as I can tell, the same fate has befallen the Virginian strawberry. There is apparently still a small but devoted following of the musk strawberry in gourmet circles in Italy (of which my wife and I are clearly not part since no restaurant in this country has ever offered us this delicacy). And the Chilean strawberry is still eaten in certain parts of southern Chile.

And what of the other species of strawberries? Because there are something like 15 other species of strawberries around the world. Not surprisingly (strawberry plants liking cool to cold conditions), most of these are native to northern Eurasia, in an arc going from western Siberia to northern Japan. But a number are also to be found in the high areas of western China, all the way from Qinghai in the north to Yunnan in the south. A couple of species are also found in the Himalayas proper. There is even one species which inhabits the hill country of southern India and the mountainous regions of the Philippines.

A good few of these species don’t produce a fruit worth eating. Others do, but the steamroller of the garden strawberry hybrid has meant that they have never had a chance to develop commercially. They are only eaten locally. This is especially true in China. I find that a pity. Rather than becoming the biggest global producer of what is essentially an American hybrid, China should look to its own strawberries and bring them to its people, and to the rest of the world. Just a thought.

As for me and my wife, I think we should plan an enormously long hike from Yunnan to Qinghai, sampling the local strawberries along the way. That would certainly keep us busy for quite a while …

POSTSCRIPT 20 October 2020

A sharp-eyed, and knowledgeable, reader recently informed me that I had made a fundamental mistake when I thought that the little red fruits I was seeing on those hikes with my wife were woodland strawberries. Actually, he kindly told me, they were false strawberries (or mock strawberries), Potentilla indica. The fruits look like the Real McCoy, the leaves look like the Real McCoy, but it ain’t the Real McCoy! After a moment of indignation against this plant masquerading as another, I actually felt relieved. I wrote above that the fruits which I had tasted were bland tasting. Actually, eating them was like eating paper filled with sand (the keen-eyed reader felt it was like eating styrofoam; the few times I’ve bitten into styrofoam makes me think that that taste is quite nice compared to what I was tasting). I kept on wondering how our ancestors could ever have thought they were nice to eat. Now I know that what they were eating – the Real Mccoy – probably tastes quite nice, and I look forward to coming across some in next year’s hikes.

This discovery that what I had been looking at was actually Potentilla indica led me of course to do my usual (Wikipedia-based) research. Which in turn led me to discover that this false-friend is actually native to southern and eastern Asia. Another invasive species! Any faithful reader of mine will know that this has been a topic on which I’ve written several posts over the years. If any of my readers happen to live in Minnesota, they should be aware of the fact that that State’s Department of Natural Resources invites people to report this plant (and any other invasive species) to the authorities. I’m not sure if Italy has any such reporting system, but if it does I will be sure to report any more patches of this fake strawberry which I come across to the right authorities, and will gladly help them in uprooting the little bastards.