John Singer Sargent’s ‘Man Reading’

by mitchellgallery

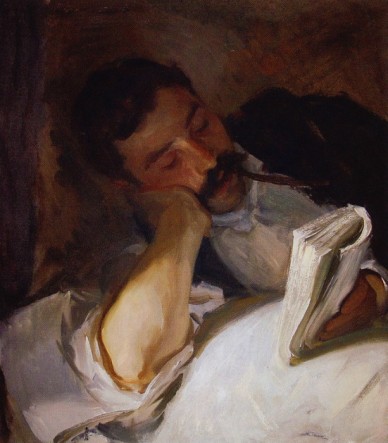

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Man Reading (Nicola D’Inverno). Oil on canvas. Reading Public Museum.

This painting by John Singer Sargent is one of my favorites in the exhibit. It stands out to me as the most intimate of the Impressionist scenes. Among the many paintings of landscapes, only a few depict people, but do so at a distance; a woman in a white dress standing inaccessible on a distant hill, or a seated woman turning her head entirely away from the viewer. People in those paintings come across less as the subjects in their own right, and more as parts of the greater scene around them.

But this painting above is concerned primarily with a human subject, and I would say it goes so far as to do something none of the other Impressionist paintings in this exhibit do: it suggests the inner life of this person. That this man might be depicted as a world unto himself, and not just a peripheral element of the artist’s impression of a more general scene seems like a striking departure from the pure Impressionist tradition.

Yet the painting is still Impressionist in its style. The form of the man reading is not carefully and sharply delineated, but instead built up of lively, spontaneous brushstrokes. Around his head, these strokes are formed into a kind of halo, radiating out along the curve of his head. He is totally absorbed in reading. From the outside, the act of reading is a quiet, absorbing, contemplative one. But Sargent has captured the motion in this activity with his brushstrokes. The way the pages are painted dynamically, even roughly, as if taught with the tension with which his hand hold them.

As the reader retreats inward in thought, Sargent paints the man as half-withdrawn into a shadowy nook. But two parts of the painting stand out, illuminated in sunlight: The man’s forearm, and also the pages of the book he’s absorbed in. The most dynamic, even careless, brushstrokes form the pages of his book, which the man grips with a kind of energy absent in the rest of his languid pose.

But this painting, unlike its neighbors in the exhibition, is not totally awash in hundreds of small, vibrant brushstrokes that give the impression of a swirling, pulsating world of motion. The motion is concentrated here in the pages of the book, the focal point of this man’s world. But what the content of this world is, we can only guess at; it is his alone. The element of inaccessibility means that his inner life is not knowable, but only suggested. In this way, the painting really is Impressionist. We can’t know the subject as himself, but we are made aware of his own perceptive capacity, separate from ours, in the depiction of him reading a book.

__

Sophy Schulman — St. John’s College Student