When we ingest a plant, as food or as a medicine, we not only intake substances and active principles, but we also ingest archetypes and symbols. Our interaction with plants never occurs only on the physical plane, but also (and above all) on the energetic-functional level. And this is all the more true the more the plant-based preparations we ingest are not very elaborate: herbal teas, decoctions, tinctures, infused vinegars, infused oils convey energy principles much better than preparations that are more elaborate (such as dry extracts).

The very preparation of such simple remedies is a complex sensorial experience and, if we prepare ourselves for it with the right attention and awareness, it becomes an important learning moment.

A couple of days ago I prepared a tincture with field elm leaves, a simple therapeutic aid, probably used less than it should, given its power and versatility.

The elm tree has its own peculiarities. Viewed from afar when it is covered with leaves, it has a profile that resembles that of oaks, so much so that at a first glance the two trees could be confused with each other. If we get closer, however, we begin to notice important differences. First, the branches of the elm in some individuals are covered with characteristic “winged” corky growths (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Corky “wings” typically found on the elm branches

Fig. 1: Corky “wings” typically found on the elm branches

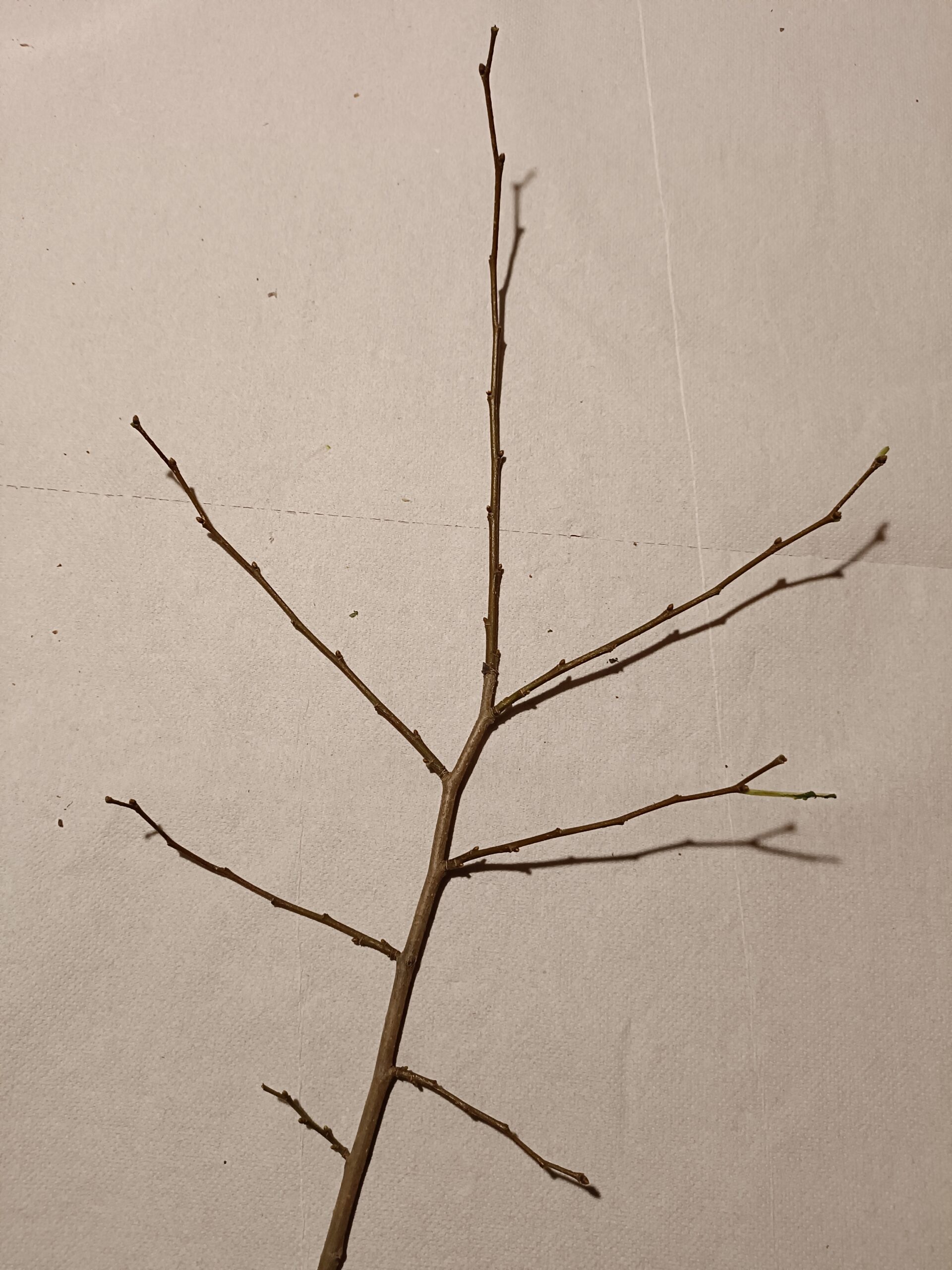

Even the arrangement of the branches has something special. The young twigs, in fact, grow on the main branch arranging themselves on a plane rather in the whole space. In botanical terms, the twigs have a distichous arrangement and, in addition, they are acrotonic (the distal ones are longer than the proximal ones). This gives the ensemble of young branches with their respective second-order twigs an almost “flat” appearance and a shape that reminds that of the bones of a hand or rather of a television antenna (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Young elm twig – distichous arrangement (on a plane)

Fig. 2: Young elm twig – distichous arrangement (on a plane)

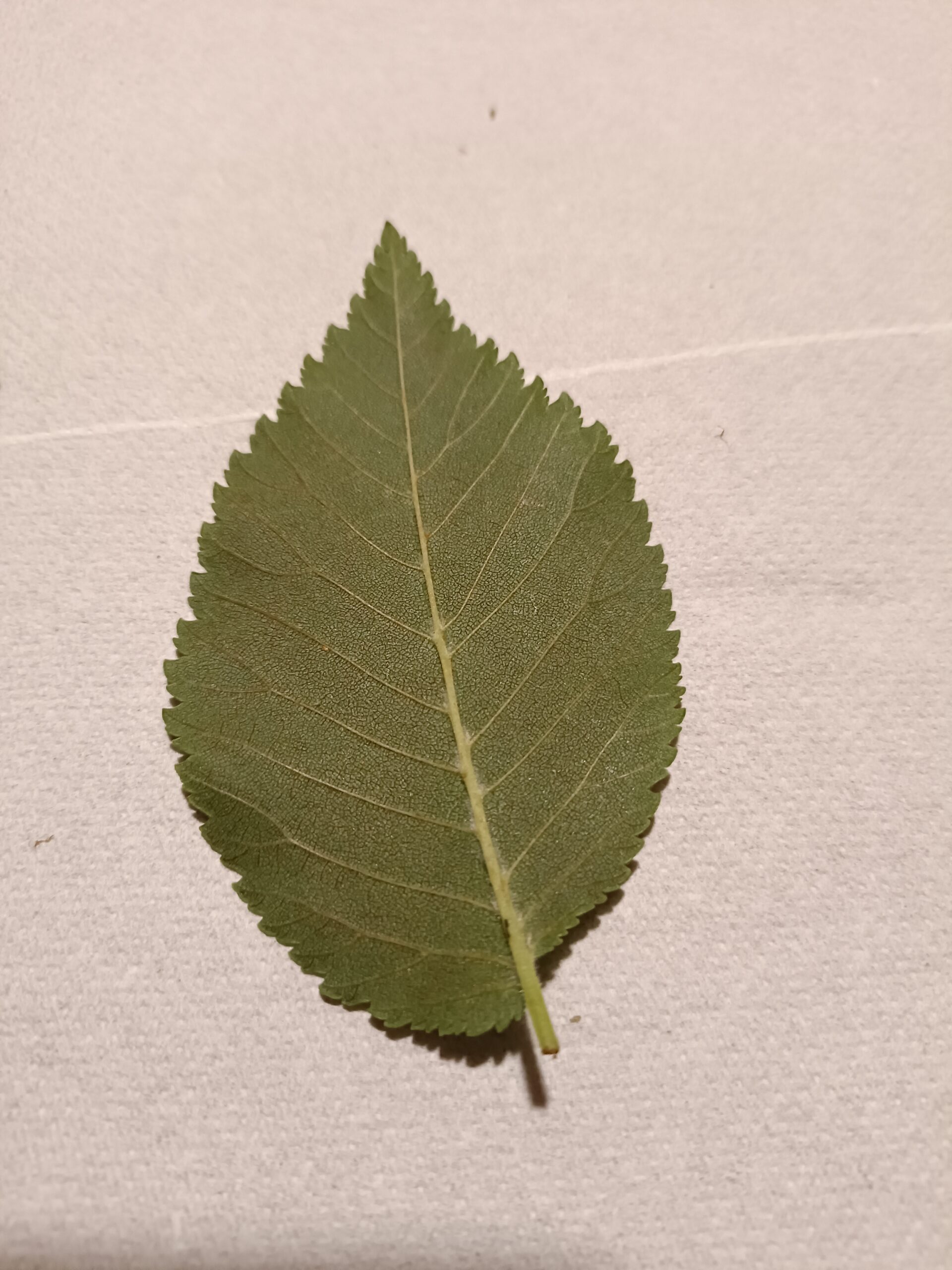

Elm leaves have their own peculiarities, too. First of all, they, too, are arranged in a distichous manner (that is, in an alternating-opposite way on a plane) and in addition, unlike what happens for most trees, they are asymmetrical with respect to the leaf axis: the base of the leaf is wider on the side towards the branch (in other words, if the bud from which the leaf originated was on the left side of the branch, then the right half of the leaf is more developed and vice versa). Even in the domain of the leaves, therefore, the elm creates a particular order (figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3: Upper surface of an elm leaf |

Fig. 4: Lower surface of an elm leaf |

Together, the presence of the corky growths, the particular (almost essential and “rigid”) structure of the branches and the shape and arrangement of the leaves suggest us that the elm tree is particularly linked to the “ideas” of structure and structuration, or rather to their relative “principles”: the tree takes advantage of the space not in an “undisciplined” and “casual” way, but in a specially ordered and highly structured way.

Furthermore, if we touch a mature elm leaf we can notice that the upper surface is rough and covered with tiny scales that seem almost mineral to the touch, hard and with a certain rigidity. They almost seem not to belong to the soft “nature” of the leaf. This “mineral roughness” indicates the presence of a good amount of silica in the plant, which is also confirmed by the hardness that the wood assumes when the tree grows in a soil particularly rich in this mineral.

The lower leaf surface, on the other hand, is covered with a velvety tomentum that caresses the skin and seems to communicate a certain soothing capacity even to the touch: in fact, the elm is also particularly rich in mucilages which render its preparations decidedly soothing and emollient.

Shortly after being harvested, the leaves give off a strong and characteristic sweet smell that clearly indicates the presence of coumarins, molecules that provide the plant with a thinning (but not anticoagulant!) activity on the body fluids; when they are crushed, before being put in the hydroalcoholic solvent, the leaves instead give off an odor that is typical of some organic acids (e.g., oxalic), this time indicating a “refreshing” property of the elm.

If the making of a tincture communicates all this to us, even more so our body “absorbs” information when we ingest it. Information that – as we have seen – are clearly present to our senses even when we directly interact with the plant: they are the so-called “signatures” that our Ancients knew well how to grasp (therefore little or nothing to do with the usual and “banal” – even if not groundless – walnut kernel-brain association) and that we must re-learn if we want to make ourselves free from the analytical vision of the modern herbal medicine that provides us only information related to the matter and not to the subtle actions of the remedies.

Elm is traditionally associated with the Jovian (according to some alchemical authors) or Mercurian (e.g., according to Steiner) archetypes and functions. However, its ability to act on the “interfaces” (skin, mucous membranes, serous membranes, connective tissue, wounds, fractures) and on the lungs makes it a decidedly Mercurian plant (and the symbolism and myths associated with the tree confirm such correspondence). Its “structuring” ability (for example, related to its capacity of healing wounds and strengthens bones) could refer to a secondary Saturnine function (not primary, as the tree is not an evergreen).