Pictish Culture: Art, Mythology, Attire

The ancient Picts of Scotland were far more sophisticated than previously believed.

The ancient Picts of Scotland were far more sophisticated than previously believed.

Table of Contents

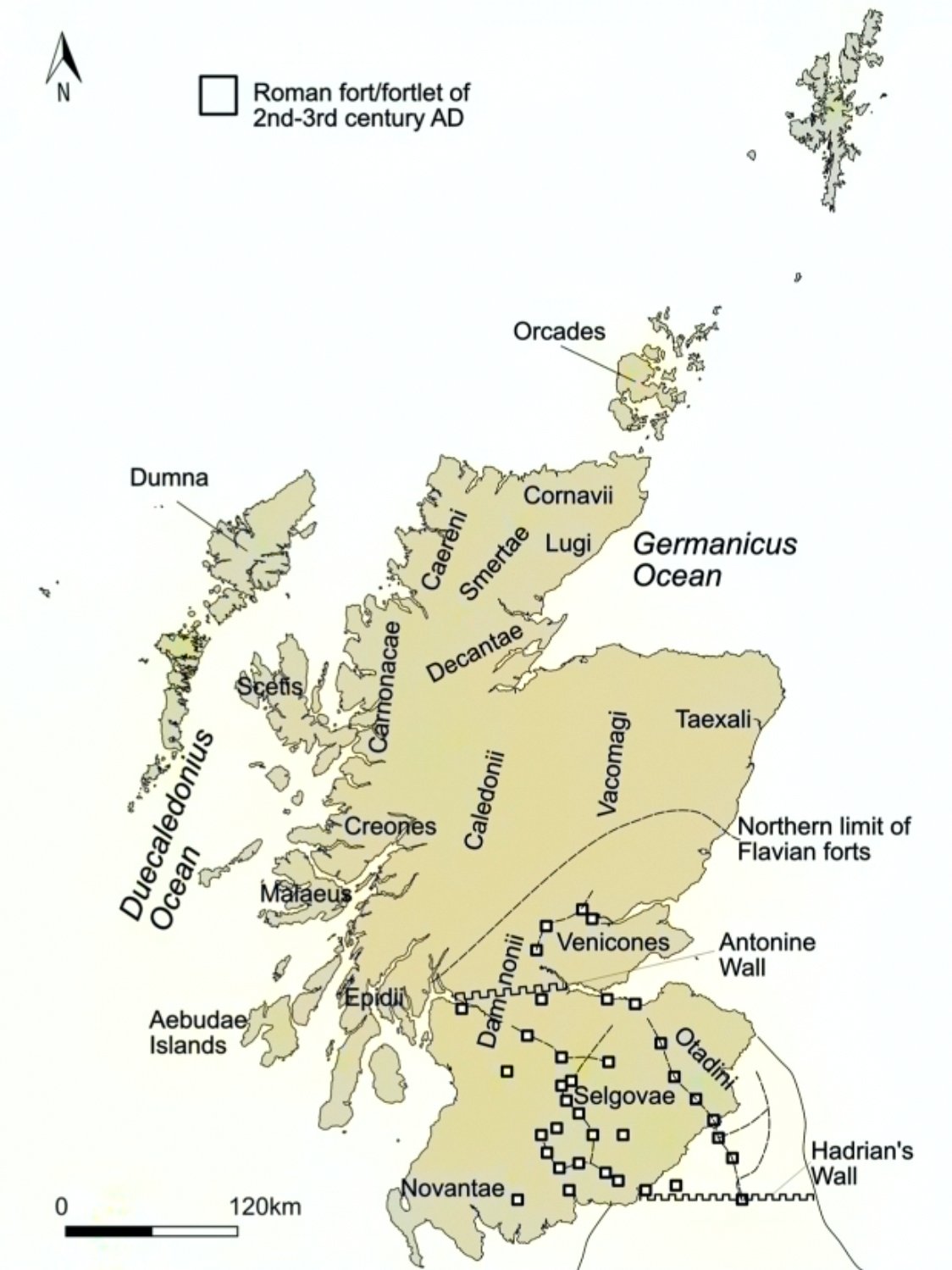

ToggleThe Picts of Northern Scotland are often considered the oldest indigenous group of the British Isles. Following the invasion of Julius Caesar in 55 BCE, individual tribes, including the revered Caledonii, began forming a confederacy known by Latin writers of the 4th century as the Picts. Forced to unify themselves at the threat of the encroaching borders of Rome’s Province of Britannia, the Picts would grudgingly fight to remain independent for over three centuries.

The Picts left behind little to no written evidence for modern historians to study. Though recently, archaeological excavations, the study of Pictish carved stones, and medieval manuscripts have been used to decipher the complex and unique cultural history and heritage of these ancient peoples. And their story is far greater than the Latin scholars gave them credit for.

According to ancient Greek writers, the pre-Roman inhabitants of the British Isles were known as the Pretani, an indigenous name possibly used by the tribes themselves. By the 4th century CE, the tribes who lived beyond the northern border of the Roman Province of Britannia were referred to as the Picts, fierce indigenous warriors who wanted no part in the customs of Rome.

One legend of their origin is preserved in the Pictish Chronicles, a collection of medieval manuscripts based on oral legends. In the text, the first ruler of the Picts was a king known as Cruithne. A similar myth is preserved in the later Irish ‘Book of Lecan,’ written in the 14th century.

Both manuscripts proclaimed that Cruithne had seven sons and divided the territory of Northern Scotland among them. Historians believe that the individual descendants, known as Cait, Cirig, Ce, Fib, Fidach, Fotla, and Fortrenn, each symbolically became the great ancestor of a clan of Northern Scotland.

Many academics believe that the earliest Pictish peoples lived on both sides of the Irish Sea. There is some evidence to support the claim that the Picts were not only residents of Scotland, but Ireland as well. The etymology of the word Cruithne, an Irish Q-Celtic word, is the equivalent of the P-Celtic Pretani, the name used by the earliest Greek writers to refer to the native inhabitants of Britain.

Nonetheless, it’s generally considered the Picts and their predecessors had formed a confederation that inhabited and controlled Scotland from around 79 until 843 CE.

While little historical writing has survived on how the Picts lived during the confederacy, archaeological evidence has provided some insight into this unique culture.

The Pictish Confederacy was likely composed of townships and rural communities as opposed to large cities. However, there were extensive settlements spread throughout Northern Scotland. The communities sat perched atop mountains or on vast plains, within coastal and hill forts that often boasted massive defensive walls and ramparts.

Early manuscripts speak of the Kingdom of Fortriu as one of the major settlements from the 4th century CE. According to experts, the tribal chief of the Kingdom of Fortriu was synonymous with the King of the Picts. Archaeologists have long believed that the kingdom lay somewhere in the vicinity of Perth. Though recent excavations in the town of Moray and the ancient promontory fort of Burghead, have led many to surmise that Burghead was, in fact, the center of Fortriu.

According to archaeologists, Burghead Fort is the largest Pictish fort ever discovered. Burghead saw its great prosperity during the 4th to 9th centuries, but the surrounding area has likely been inhabited for much longer. Some have even suggested it may be the ‘Pinnata Castra’ mentioned in Ptolemy’s 2nd-century work, Geographia. Unfortunately, most of Burghead Fort was destroyed when the small coastal town of Burghead was under vast reconstruction at the beginning of the 19th century.

However, recent excavations have revealed it was an enormous site consisting of a walled enclosure that measured over 1,000 feet in length and around 600 feet wide. In total, the site occupied a territory of over twelve acres, and within the enclosure, archaeologists have discovered the remains of various structures, including a citadel or ceremonial center.

Over twenty carved stones have been recovered from Burghead alongside other items of antiquity, including metal weapons, tools, and jewelry, such as hair and dress pins. The discovery of homes, burials, and artifacts has been enough for researchers to surmise this ancient Pictish site was extremely important and densely populated.

The Picts left behind no native manuscript that would shed insight into their extensive history. Nor have historians been able to say for sure what language they spoke. Besides what has been unearthed at sites such as Burghead, the most prevalent means of gaining insight into the Pictish way of life is through the iconic Pictish Stones that have been discovered across Scotland.

The oldest of these stones were carved between the 3rd and 7th centuries. The unique stones are full of symbols, zoomorphic images, humanoid figures, and supernatural beasts. They could carve an array of animals, including wolves, fish, birds, and other glyphs, with a singular line and produce a naturalistic drawing. One glance at the carving is enough to surmise the Picts were extraordinary artists, rivaling any artistry found around Europe at the time.

One of the most famous recurring symbols of Pictish iconography is known to archaeologists as ‘The Beast.’ Its true meaning has puzzled researchers for well over a century. Some experts have put forth the idea that it resembles a dolphin, yet unlike other animals who are clearly identified on Pictish stones, this remains a mystery. Another reasonably common symbol is the Crescent V-Rod; thought to represent the sun or moon, it may suggest that the Picts held beliefs that were influenced by the movement of celestial bodies.

While the imagery of the Pictish Stones is open to interpretation, most scholars will generally agree that many of the depictions are stories centered on great battles or mythological legends. Numerous experts have gone as far as to suggest that the symbols represent some kind of hieroglyphic writing system. Unfortunately for scholars, there is no Rosetta Stone that would enable them to decode the messages left behind.

During the Roman occupation of the British Isles, Latin scholars ensured that the wider Empire believed those who lived to the North of Britannia were nothing but naked savages. This idea was further emphasized in the modern era with drawings by 16th-century writer John White. Though researchers now know this was certainly not the case.

In reality, the Picts took great care of their appearance. On various depictions left behind on their enigmatic stones, there are fully dressed males and females with long groomed hair and beards. Historians also know that by at least the 5th century, the Pictish people made use of wool, linen, and silk, to craft clothing, including tunics and coats. Cloaks and capes would have adorned the outside of their outfits, which would have held up against the harsh weather of Northern Scotland.

It’s thought the Picts wore tartan trousers made from the sheep’s wool. One surviving piece of evidence to support this theory is found nearly 2,000 miles away in Morocco in a bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Caracalla. Alongside the Emperor in the depiction is a Caledonian or Pictish warrior. He’s dressed in what appears to be a pair of plaid trousers.

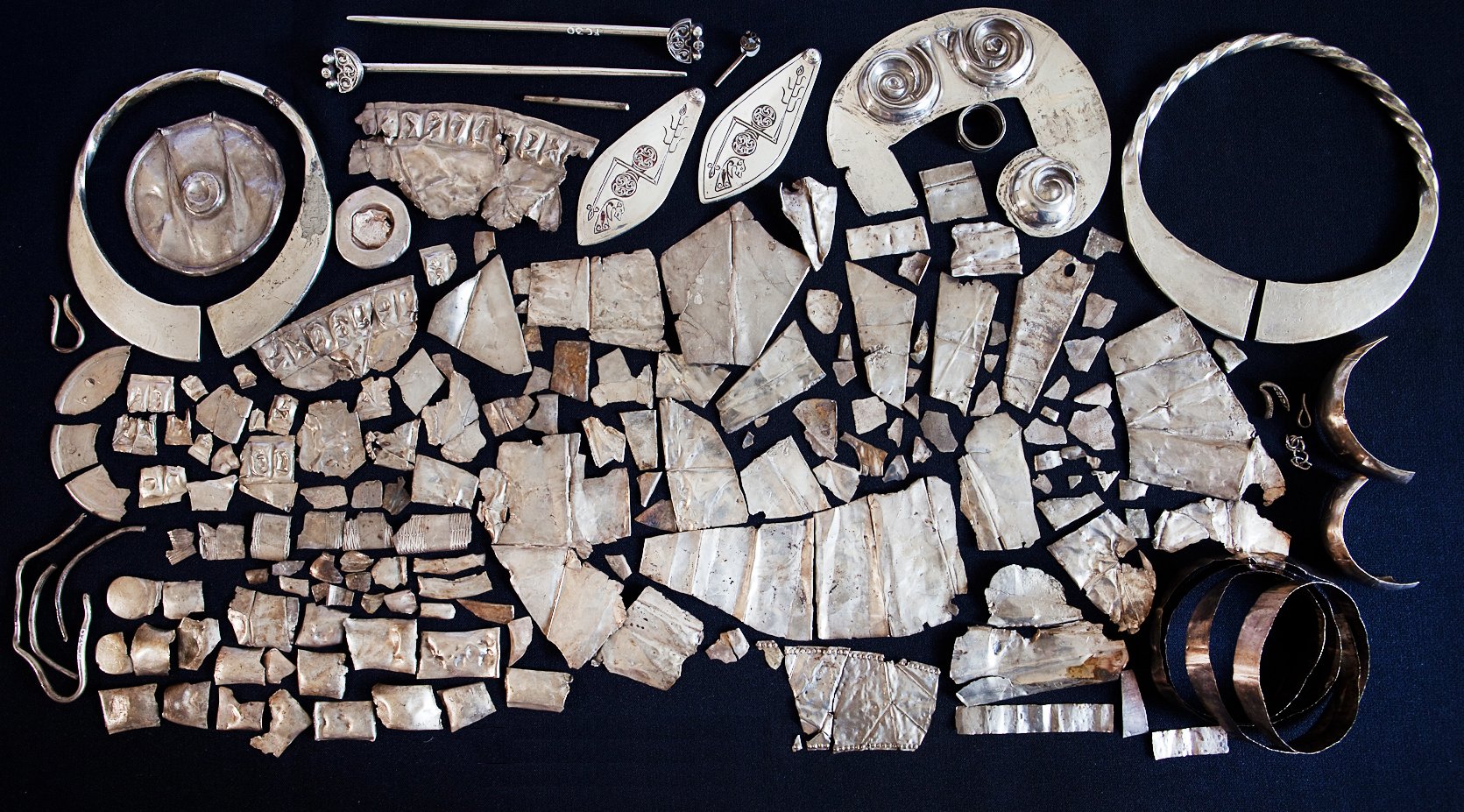

The Picts also preferred to accompany their thick clothing with silver jewelry. While Scotland isn’t known for silver mines, it’s possible the Picts accumulated a vast portion of this metal during their raids on the Roman Province of Britannia in the south.

Norrie’s Law Hoard, dated to around 500 CE, is one of the largest Pictish hoards ever discovered, made up of 170 silver pieces. The most impressive is a silver plaque decorated with unique Pictish symbols, though the collection also includes several complete items, such as a spiral ring, a large broach, and a hairpin.

Early Pictish religious beliefs are still a mystery. Though some carvings and archeological evidence suggest they followed a polytheist pantheon of deities, similar to the Celtic peoples. One theory hypothesizes that the Picts may have practiced a religion similar to Druidism, as their neighbors in the south did.

Although for centuries, the Picts were considered violent barbarians, in reality, they were peaceful farmers who shared a close connection to nature through their religious beliefs. According to a few experts, the Picts believed that goddesses had once walked the land, and this is what made their territory sacred. So it’s no surprise that the Picts fiercely committed to protecting their lands against all foreign invasion, whether it be the Romans, or later Scots, Anglos, and Normans.

Such a belief in goddesses contributes to the theory that the Picts followed a matrilineal succession, where the kingship was decided from the mother’s side and not the father’s.

Though aspects of the Pict’s ancient religion remain, by the 4th century, Christian missionaries had begun preaching throughout the land. By the end of the 6th century, a significant portion of their population had been converted, due in large part to the Irish monk Saint Columba. In the centuries that followed, Pictish culture changed dramatically, including the stone iconography, which then leaned more towards Christianized carvings.

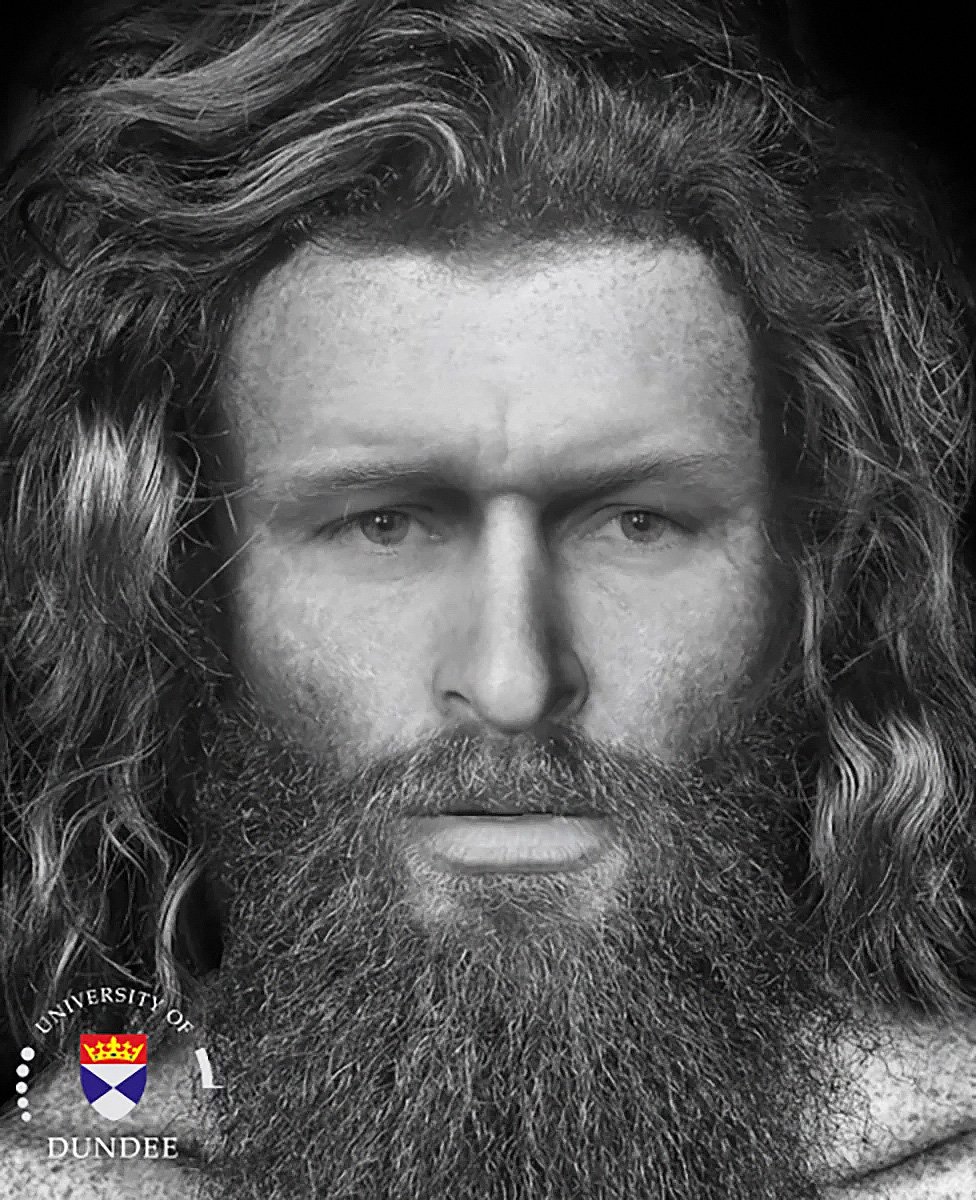

While the evidence discovered gives some insight into how the Picts dressed and the religion they practiced, there are very few sources that describe what they looked like. According to the writings of Tacitus, who accompanied Agrilocla on his invasion of the North during the 1st century CE, many of the Caledonians were red-haired and large-limed.

A reconstruction of the face of a Pictish man who lived over 1,400 years ago and whose remains were discovered in Black Isle, Ross-shire, has shed more light on how a portion of these ancient people looked. He had a full, thick beard and long wavy hair. In general, the Pictish man is remarkably similar to those living in Scotland and Northern Ireland today.

Just as Tacitus mentioned, the earliest inhabitants of Scotland had the gene for red and blonde hair. However, many also had dark brown hair. The unique and varying characteristics may relate to the widely held idea that the Pictish peoples were made up of various ethnic groups with distinct origins.

To many, it seemed as though the Pictish culture suddenly vanished from the face of the earth during the early medieval period. However, the Picts were not gone, they simply unified with the Scots, a branch of the Erainn or ancient Irish known as the Dal Riada.

Exactly what forced the Picts to join the Scots of the Western Highlands is uncertain. Though, some theorize that excessive defeats at the hands of the Vikings left the Pictish kingdom fractured and in need of support. After the death of their final recorded Pictish king in 843 CE, it seems they unified with the Dal Riada in order to protect their ancestral territory from future Viking raids.

The first king of the united Scots and Picts was Kenneth MacAlpin, who supposedly had a Pictish mother and a Scots father. King MacAlpin ruled over the newly unified kingdom of south and central Scotland, which was known as Alba.

The unification may have saved many Pictish lives, though unfortunately, with it came the eventual downfall of the ancient Pictish culture. Due to Christian and Gaelic influence, the Picts slowly forgot their ancient ways, and by the Middle Ages, the descendants of the once great Pictish people were simply members of the Kingdom of Scotland.