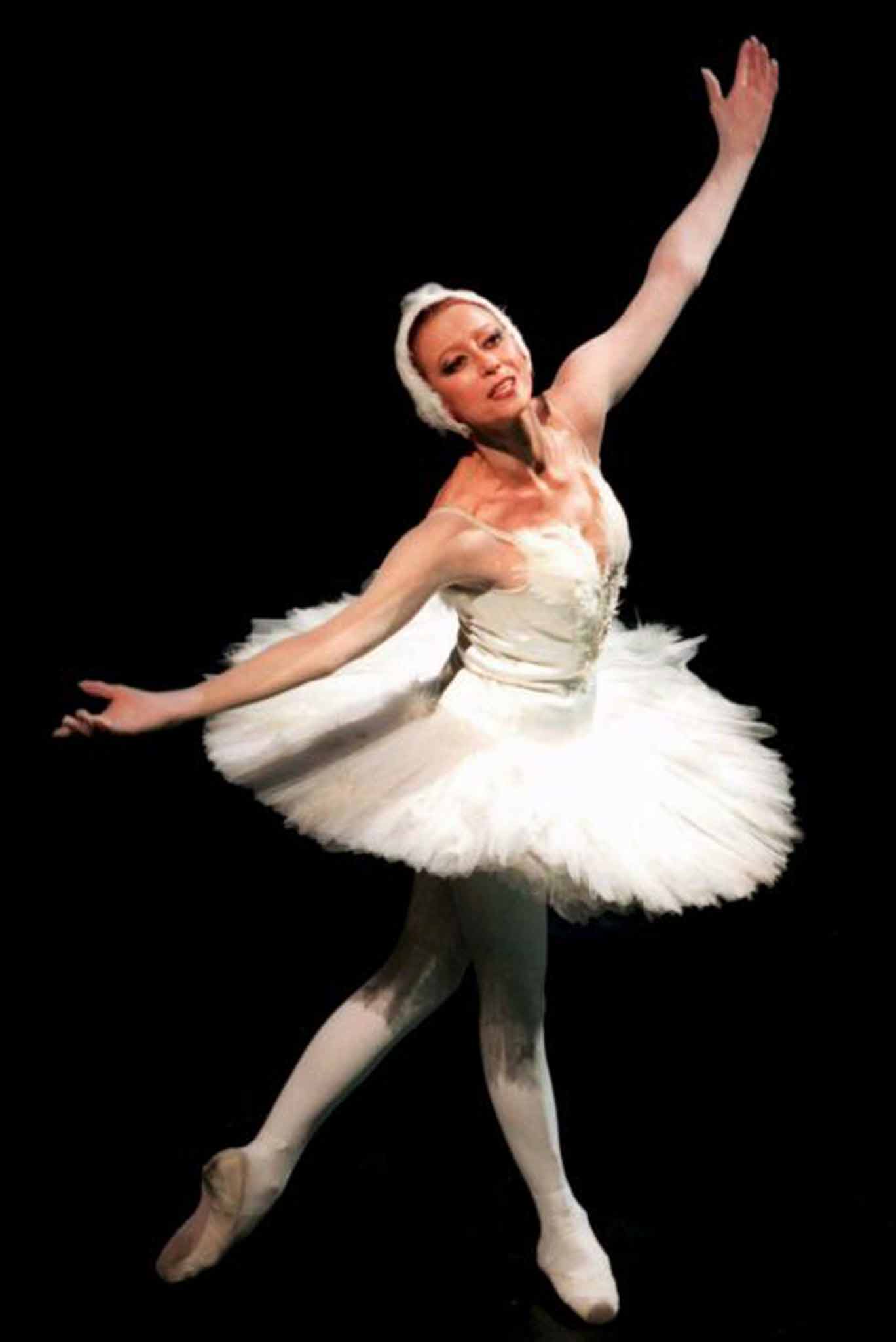

Maya Plisetskaya: Ballerina whose charisma and talent helped her fight the Soviet authorities and achieve international fame

Renowned for her interpretation of Swan Lake, she was also associated with modern roles that allowed her to try new forms of movement

If Soviet ballet's most famous ballerina was Galina Ulanova – arguably also the 20th century's greatest – then Maya Plisetskaya was not far behind. On Ulanova's retirement in 1962 she became the Bolshoi's prima ballerina; her celebrity in Russia was on a par with cosmonauts and film stars; her distinctively tall and dramatic image, captured in photos and film, was as familiar as Khrushchev's.

She impressed audiences with her virtuosity and the special emphasis she gave to her long, supple arms. She compelled them with her remarkable acting powers – usually dealing in heroic, powerful characterisations. She was renowned for her interpretation of Swan Lake and The Dying Swan, giving these swan characters a new dark passion. But she was also associated with modern roles that allowed her to try new forms of movement and satisfy her liking for strong-coloured personalities.

Invited to the White House, fêted by Hollywood stars, escorted by Bobby Kennedy, helped by Pierre Cardin (who designed some of her costumes), she had to wait some time before achieving this recognition in the West. Where Ulanova adhered to Soviet orthodoxies, Plisetskaya was the opposite in every sense and consequently forbidden foreign travel.

Not only was she born Jewish in a society that discriminated against Jews, she was also, by dint of childhood tragedy (her parents were victims of Stalin's purges), considered politically "immature". So she began as a square peg in a round hole – and continued to struggle against the black mark next to her name. Her story is therefore the story of Soviet society, not far removed from Swan Lake: she was an individual longing to fly freely but imprisoned by the grim Soviet machinery. Later, she was to use her talent and celebrity as a lever to gain some of the opportunities she hankered after.

"Do you ever go full-out at rehearsal?" the French choreographer Roland Petit once asked her, irritated by her practice of simply "marking". "No," she replied, "because I want to dance to 100." And she did dance a long time, performing major virtuosic roles into her late fifties, smaller solos beyond, and always looking 20 years younger than her real age. But she had good genes. Youthful longevity marked the large Messerer family, which included her aunt Sulamith and uncle Asaf, both leading Bolshoi dancers. Born in Moscow in 1925, Plisetskaya started the second generation, followed by her younger brother Azary Plisetsky, who danced with the Cuban National Ballet, and her cousins Boris Messerer, a successful stage designer, and Mikhail Messerer, a dance teacher.

Her mother Rakhil was a film actress (as Ra Messerer) before marrying her father, ME Plisetsky, an engineer and high-principled Communist who was promoted to run the offices of Arktikugel (Arctic Coal) in Barentsburg off the coast of Norway. The family success was short-lived, however. Unable to compromise the sincerity of his socialist beliefs with Stalinist ideology, he found himself in disfavour. Although brought back to Moscow on apparent promotion, he was thrown out of the Communist Party and arrested. He was executed in 1938 (and later rehabilitated). The family learnt of his death only afterwards.

Ra was imprisoned with her third child – a baby boy, Azary – and sent to Siberia. Maya and her young brother were in the care of Sulamith and Asaf. None of them knew that Ra was being sent to Siberia. They found out only through one of those extraordinary acts that occur in extreme times: crowded into a transport train with her baby, Ra managed to throw out a note to a woman guarding a crossing. Ra had scribbled with a matchstick on a tiny scrap of paper Sulamith's address and the words "taken camp Akmolinsk Oblast".

Maya had entered the Bolshoi school in 1934. Her mother returned from exile in April 1941 and that September, with the start of hostilities with Germany, she and her children left for Sverdlosk in the mistaken belief that the Bolshoi was moving there. Worried that without regular training she would jeopardise her future, Maya returned to Moscow alone.

For her first important recital as a student she danced Impromptu, by the modernist choreographer Leonid Yacobson (as a first-year student, she had appeared in a Yacobson piece called Disarmament Conference). Her student performances at the Bolshoi Filial Theatre were noticed for their exceptional virtuosity and, when she graduated in 1943 she entered the Bolshoi company as a soloist. Her company debut was as one of eight nymphs in a dance section of the opera Ivan Susanin. Her first featured role was the mazurka solo in Chopiniana (Les Sylphides). She then danced the Queen of the Wilis in Giselle, a part in keeping with her charisma, far removed from the ballet's shy and gentle titular heroine.

She was never to dance that heroine, normally a pivotal role in the history of any major ballerina. But she notched up many other leading roles, even if the procession of Swan Lakes, de rigueur for visiting dignitaries, seemed endless, so much so that Khrushchev complained to her of Swan Lake fatigue. By her count she danced Odette-Odile 800 times over 30 years, in Moscow and elsewhere. In Moscow she danced it for Mao Zedong and Stalin; in Washington for John Kennedy, who was rebuilding Soviet relations after the Cuban missile crisis.

Her other classical roles included the title part in Raymonda, Kitri in Don Quixote, the Tsarevna in The Humpbacked Horse (she also starred in the 1961 film) and Aurora in Yuri Grigorovich's staging of Sleeping Beauty. Her most frequent partner was Nikolai Fadeyechev. The young Rudolf Nureyev, briefly in Moscow, saw her debut as Kitri and, according to her autobiography I, Maya Plisetskaya, said: "I sobbed from happiness. You set the stage on fire."

Because she was always ready to interpret new ballets she was at the heart of Soviet choreography. She danced two versions of The Stone Flower (to Prokofiev's score); created the central role of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain in both Lavrovsky's production (1954) and Grigorovich's (1959) Bolshoi restaging of his own Kirov version. As such, she was the central character: a magically omnipotent creature, benevolent to the good inhabitants, merciless to their oppressors. Appearing sometimes as a beautiful woman, sometimes as a lizard, acrobatically entwining itself, the character gave full rein to her dramatic and technical versatility.

She also created the role of Aegina in Moiseyev's Spartacus (1958); later she danced the more lyrical Phrygia in Yacobsen's version (1962), displaying her powerful gift for tragedy. She was Suimbide, the bird-girl, at the Moscow premiere of Yacobsen's Shuraleh, based on Tartar folklore. In Rostislav Zakharov's popular Fountain of Bakhchisarai, as Zarema, she was one of the two female leads and appeared opposite Ulanova's Maria in the film version. And in Chabukiani's Laurentia she gave full verve to the titular heroine, finding in her a Spanish spirit close to her heart.

Behind the scenes she was dealing with the Soviet authorities. In 1949 she was chosen to appear in a Kremlin recital for Stalin's 70th birthday, dancing before Stalin and Mao Zedong in a tense atmosphere. With Stalin's death in 1953 came a shift in etiquette: receptions for foreign politicians became frequent and artists were used to liven up the mass of grey bureaucrats. She used her growing fame to buttonhole diplomats and politicians, foreign and domestic, and complain about being blacklisted for touring. Tailed by KGB agents, she wrote pleading letters. She got support from Khrushchev's son-in-law Viktor Gontar, but his attempt to help earned him disfavour.

When the Bolshoi made its first visit to London in 1956 she was forced to remain behind. Her performance of Swan Lake in the main company's absence was filled by her fans. So afraid were the KGB and the Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva, of a demonstration that they placed security men around the theatre boxes to grab spectators if they applauded too loudly. The resulting mayhem became known as The Battle of the Boxes. It was another two years before she was granted permission to travel abroad, to Prague – behind the Iron Curtain.

In 1958 she married the composer Rodion Shchedrin. In 1959, thanks to his and friends' machinations, as well as support from Khrushchev, she was finally allowed to take part in the Bolshoi's US tour and make her Western debut with Swan Lake. She was constantly shadowed by minders, but even without them, she said she would not have defected. Khrushchev had put his faith in her, and abandoning her family and homeland and beloved Bolshoi stage would never have entered her mind.

In 1963, after a second US tour (1962), she finally appeared with the Bolshoi in London, where she secretly met Nureyev (she was later to act as one of his emissaries, carrying parcels to his family). In 1965 she was in St Paul-de-Vence, posing for the émigré Russian painter Marc Chagall. In 1966, on yet another New York tour, she took part in a gala closing the old Metropolitan Opera House and danced The Dying Swan to Isaac Stern's solo violin. Two years later she danced the same piece in the new Metropolitan Opera House, as a homage to Bobby Kennedy, fatally shot the previous day. As she started dancing, the audience stood, some of them crying; when she finished, there was no applause, just silence.

Longing for new roles, she invited the Cuban Alberto Alonso to choreograph Carmen. Shchedrin made a montage of his and Bizet's music, and the piece premiered in 1967, conducted by Gennady Rozhdestvensky and designed by her cousin, Boris Messerer. It was coolly received and the second performance cancelled. This was reinstated only after frantic representations and a promise to Furtseva to cut out the semi-erotic movements. Eventually, it became one of her most popular roles.

In 1973 Roland Petit was the first Western choreographer to work with her, making La Rose Malade, a 12-minute pas de deux based on Blake's poem and premiered in Paris. She was to dance this all over the world with various partners. She then worked with Maurice Béjart, performing his Bolero for stage and film. Béjart went on to choreograph Isadora, premiered in Monaco (where Duncan had died) in 1976, and to stage his Leda with her in Moscow in 1979.

In 1968 she had appeared as an actress (playing Betsy Tverskaya) in a film of Anna Karenina, for which her husband had written the score. This helped sow an ambition to perform a dance version. After the usual battles with Furtseva and others, she received permission in 1972 to stage a ballet at the Bolshoi Theatre, becoming a choreographer by default. This was widely toured and staged, and filmed in 1974. She then choreographed The Seagull in 1980 (unseen by Furtseva, who had by then killed herself with cyanide) and Lady with a Dog (1985).

In 1983-84 she was ballet director of the Rome Opera; from 1987-90 artistic director of the Ballet del Teatro Lirico Nacional in Madrid, where in 1988 she commissioned and danced Jose Granero's Maria Estuardo (Mary Stuart). In 1990 she accepted an invitation to dance in Julio Lopez's El Reñidero (The Cockfight), to Astor Piazolla's music in Buenos Aires. In 1993, while dancing The Madwoman of Chaillot at the Bolshoi, she celebrated 50 years as a dancer. In 1996 she danced The Dying Swan at a gala in her honour in St Petersburg. Her 80th birthday was marked by galas in Moscow, Paris, Tokyo, and in London at the Royal Opera House. She died of a heart attack.

Maya Mikhaylovna Plisetskaya, ballet dancer: born Moscow 20 November 1925; Lenin Prize 1964; married 1958 Rodion Shchedrin; Legion d'Honneur 1986; died Munich 2 May 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies