Depending on your comfort level, the work of Joel-Peter Witkin will either attract or repulse you. Witkin, a seminal figure in the field of photography, has made a career shooting black-and-white tableaux in elegant arrangements, including still lifes and portraits, but the subject matter has remained provocative. Graphic sexual imagery, people with physical deformities, and dismembered animals and humans have all been arranged with pageantry in his dioramalike photos. Although the 15 new images on view at Andrew Smith Gallery in his solo exhibit Love and Other Reasons ... To Love contain the elements that have made him a controversial photographer, Witkin has settled into a gentler mode, presenting work less challenging, overall, to our squeamish natures, but no less concerned with references to the art-historical canon, themes of social justice, and, above all, compassion.

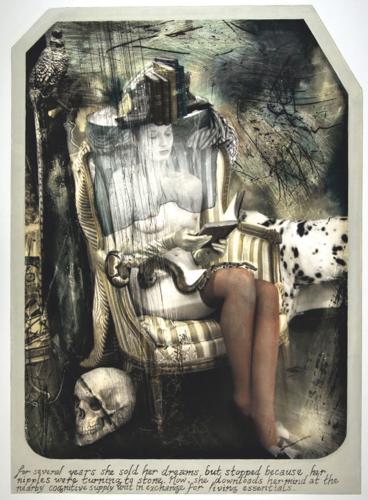

In The Reader, hand-painted and scratched to resemble an aged daguerreotype, we see a graceful portrait of a woman in a chair, book in hand, a veil obscuring her face while a serpent slithers across her lap as other animal forms surround her. On the surface, Witkin has crafted a simple arrangement, but the elements come together to suggest double meanings. The strange animal world around the woman could be an outward expression of the things she reads in books or the veil can be seen as her retreat from a threatening outer world into the safety of her interior life. A human skull rests at the foot of her chair, an image of death intended as a memento mori. “Death is a reality — the physical end of life,” Witkin told Pasatiempo. “Memento mori means ‘remember you must die.’ In art, that subject is a reminder of our mortality and is part of the art of all cultures that have existed. In our escapist, commercial culture, death is the greatest fear and the ultimate taboo. I try to remind people in my work on this subject that to understand death you must understand what life is about. Life and death are sacred times.”

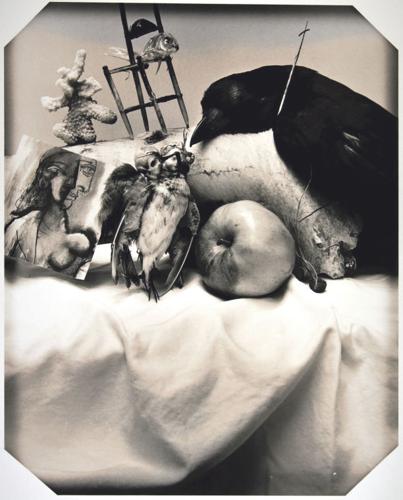

More explicit, graphic imagery greets the viewer in Our Daily Bread, depicting a prostrate human figure with two faces — one male, one female — gorging on severed male genitals. Those familiar with Witkin’s work have no need to ask whether the disembodied female head, attached to the male body by cords, is real, or the genitals for that matter. No doubt they are actual body parts. But Witkin isn’t a documentarian, capturing a moment in time or a specific incident like the aftermath of an atrocity. We don’t know why the woman in this photo lost her head, but Witkin takes the head and other elements and gives them a new context. “I bring the world, its history, and its human spirit into my studio,” he said. “There I make visual narratives of what I have combined there — of people and objects. It’s like a living sculpture taken out of time. But I don’t just record an event, I want to create an indelible human experience of what I find there and what I have discovered in myself in the process.” The chimerical figure appears Janus-like, with two faces posed in opposite directions. A mythic sensibility enters into the tableau. The genitals in the mouth of the figure’s male face make this strange picture into a kind of ouroboros, like a snake devouring its own tail.