One of the symptoms of middle age seems to be an increased awareness of my contemporaries. Somehow it seems that I’m the same age as the last prime minister, Mike Tyson and Cindy Crawford. But I’m also the same age as Adrian Mole, and this makes much more sense.

Adrian celebrated his 14th birthday with a tracksuit and football from his father, A Boy’s Book of Carpentry from Grandma Mole (“no comment”) and £1 inside a card from Grandma Sugden (“Last of the big spenders”). While I didn’t keep a diary at the time, I’m sure this list won’t have been far off. One of the great pleasures of reading at that age is a sense of “me too”, the relief and reassurance this brings, and it’s hard to think of a time when I’ve experienced a greater sense of recognition than when reading The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 ¾. The anxiety about acne and nuclear war, the perpetual sense of injustice, the anguish of the unrecognised intellectual, the reverence for the BBC and reliance on the public library in the endless quest for self-improvement, it was all here, and made blissfully funny in a sustained, near flawless piece of comic ventriloquism. Even the title had a good joke – the childish pedantry of the “¾”, an attempt at maturity that reveals its opposite. Comedy was another teenage obsession of mine, but the great tradition of British comic fiction seemed either posh – Waugh and Wodehouse – or decidedly upper middle-class. I loved Willans and Searle’s Molesworth books, but they might as well have been set on Mars for all I knew of Latin crammers and the prep-school system. There were exceptions; Billy Liar, for instance, another love-torn provincial fantasist with whom Adrian surely shares DNA, but so much other comic writing, the Pythons, Cook and Moore, even The Hitchhiker’s Guide, all had that Oxbridge tone.

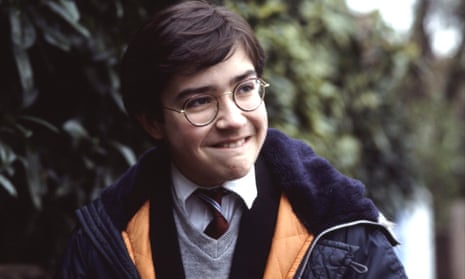

Adrian was entirely average; a middle-achieving Everyboy from the Midlands, not as posh as Pandora or Nigel, posher than the terrifying Barry Kent, unremarkable, invisible, with everything happening below the surface like, well, a mole. The Secret Diary was smartly written, stuffed full of in-jokes and references to Orwell and Flaubert and Simone de Beauvoir, but it made sense to people who weren’t quite sure what a campus looked like, and there was also a compassion so much other comedy seemed to lack. Often touching, sometimes angry, never sentimental but always sympathetic, and with an extraordinarily high joke-per-page ratio, no wonder its appeal was so immense. Boys and girls read Adrian Mole, adults and teenagers, all of us wondering the same thing: “How does Sue Townsend know?”

It helped it was so rude. When not measuring his thing or hiding in his room, “racked with sexuality”, high on Sanatogen and copies of Big and Bouncy (“Felt like I have never felt before”), he’s having wet dreams (“WD’s”) inspired by what must surely be a misreading of The Second Sex. Had anyone ever been so frank and funny about male adolescence? When Adrian writes “Woke up with a pain in my goolies”, we asked, again, how does she know?

There’s a gamble involved in returning to the books we loved in our youth, but I’m pleased to say that The Secret Diary is still wonderfully funny and entertaining. Some of that pleasure comes from a queasy nostalgia – butterscotch Instant Whip in front of Play School, Chinese chips and boil-in-the bag cod – and in this respect it’s hard to think of a better social document of a time when Lucozade was valued for its medicinal properties. Like Victoria Wood and Alan Bennett, Townsend has a brilliant ear for the precise gradations of class, the ritzy aspiration of going to Sainsbury’s or drinking wine for the first time (“it seemed a pleasant enough vintage”, writes Adrian ). As with those writers, there’s a precision to the language, an attention to economy and rhythm that is so often the mark of good comic writing; “Friday March 20th. It is the first day of Spring. The council have chopped all the elms down in Elm Tree Avenue.” Or read the great comic set piece, Class Four D’s trip to the British Museum, written in the urgent bark of a police report. (“4.30 Barry Kent disappears, last seen heading towards Soho.”) Even sitting alone, you feel compelled to read passages out loud.

There’s a wonderful rhythm, too, in the diary form itself, the set pieces punctuated with a series of tiny vignettes or one liners that at times give it the pacing of a great standup act. Townsend sets up a joke on a Monday that will pay off on Thursday, Sunday and again the following March, and the diary form makes a virtue of this kind of repetition, turning routine into comedy, and providing a terrific narrative pull for the reader. Imagine Adrian Mole, or indeed Bridget Jones, as a third-person, past-tense novel, and the story wouldn’t have nearly the same drive. Just one more entry, one more day, then we’ll put the book down.

Townsend also plays brilliantly with the contradiction of the diary form. Like a confessional or a psychiatrist’s chair, a diary offers an opportunity to be entirely open and honest, yet Adrian’s most private voice – like Bridget’s – is never entirely free from dishonesty and self-deception, so he can take War and Peace out of the library on Saturday, finish it on Sunday, and still pronounce it “quite good”. He sometimes resembles another aspirational working-class boy, Leonard Bast in Howards End, with whom he shares “the vague aspirations, the mental dishonesty, the familiarity with the outsides of books”. But there’s no condescension in Townsend’s depiction, and Adrian has a vulnerability that prevents him, for he most part, from being a pompous ass. One of the book’s smartest observations is that for all his radical posturing, Adrian is essentially conservative, fearful of change, longing for security and stability. His parents may be an embarrassment, but their break-up throws life into disarray, and the terrifying economics of the everyday are everywhere; the fear of the scene at the supermarket checkout, the unpaid bill, the bounced cheque. Townsend was an avowedly political writer, and there’s real anger in the book, yet the tone is never solemn, preachy or dogmatic. With politics, as with love and sex and culture, Adrian is just as likely to miss the point. (“Reading Animal Farm by George Orwell. I think I might like to be a vet when I grow up.”)

In the years since that first encounter, I’m afraid to say I lost touch with Adrian. Adolescence is an ordeal that we all pass through, and Adrian’s humiliations were made bearable by the hope that he might shake off the self-absorption and infatuation and find requited love or success in a vocation other than poetry. But there’s no comedy in an older, wiser, happier Mole, no story in contentment, which is perhaps why the later books, still finely written, are sometimes so melancholy and angry.

On 2 April 2007 Adrian celebrated his 40th birthday and received a Smythson A4 notebook from Pandora (claimed on parliamentary expenses), and a blow-up doll from Nigel (now blind and living with his boyfriend, Lance). Adrian has grown up into a bald, divorced father of three, struggling with a diagnosis of prostate cancer, yet he still manages to find some of his old fire. “Could the Smythson notebook and I together revive the English novel?” he wonders. Townsend herself suffered from illness throughout her life – diabetes, heart problems, arthritis and, in her final years, blindness – yet continued to work successfully at a time when most other writers might have felt justified in taking a rest.

Her death in 2014 brought the diary to an end, and we’ll never know what Adrian receives for his 50th birthday, but she was, and remains, an inspiration for a generation of readers, and writers too, a passionate popular entertainer of great integrity and wit. My own son is reading The Secret Diary now, and while he may not understand the pleasures of Pebble Mill at One or Dream Topping, he recognises skilled, truthful comic writing. It’s a pleasure to sit and watch him laugh out loud.