‘It’s been crazeeee,” Nile Rodgers says of his 65 years on the planet. We have barely met and he is already on to his parents’ heroin addiction, his mother’s three coat-hanger abortions, sexual abuse he witnessed at the convalescent home he was sent to for acute asthma as a child, mingling as a young boy with Eartha Kitt and Thelonious Monk, and life as a Black Panther in his teens. And we haven’t touched on the music – king of disco with his band Chic, supremely gifted songwriter and producer extraordinaire.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

His voice is rich – part Harvard professor, part meditation guru. There is something so mellow about Rodgers you could smoke him. But when the words sink in, your head spins. It is not just the extremes in his life, it is the frame of reference – Donald Trump casually mentioned alongside non-Euclidean geometry.

But back to his mother, Beverly. “My mom fell pregant with me at 13, then after that she didn’t want to have kids so she had three back-alley abortions. They were butchers. Really horrible.” In the end, she had five boys with five different men – all the sons became heroin addicts except for Rodgers (he preferred cocaine and booze). His biological father was also addicted to heroin, as was his stepfather. In his memoir Le Freak, he writes: “Shooting, drinking, snorting and smoking any and everything right in front of me was all part of the daily script.” He describes a family living room dotted with junkies in a state of suspended animation “like a twisted beatnik version of Ingmar Bergman’s chess game with Death”.

Aged eight, he saw a man trying to jump from the fourth floor of a New York flophouse. It was his biological father, also called Nile, whom he hadn’t seen for months. Rodgers talked him down. When his stepfather Bobby, who was white and Jewish, almost succumbed to an overdose, everyone panicked. If he had died and the dealer turned out to be black or Puerto Rican, there would have been a serious police investigation. That was when Rodgers learned the world revolved around race.

This childhood would have crushed many people. But Rodgers insists it was the making of him. The family home was artistic, bohemian, intellectual. He was treated as an equal (when not having to look after his parents). His mother was smart, gorgeous and like a sister to him (“Everybody else’s mothers looked like grandmothers, but my mom looked like a hottie”), his father was a top percussionist (“The only black person that would routinely play with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra”), his stepfather a gifted mathematician. “They were high-functioning addicts. Always. I inherited that gene.” He grins. “All of them held down jobs. My stepfather was in the schmutter trade. All my brothers worked for my uncle, who had a clothing line on the Lower East Side. That’s why they were able to become heroin addicts because they all had jobs. They were beatniks, they were cool, and they had money to throw around, and they threw it around on heroin.”

There was even a family snobbery about heroin. Bobby spent his final days in a Veterans Association home. He was admitted as an alcoholic, but rejected the label. “My stepfather was a rampant alcoholic, but he couldn’t identify as one. They almost didn’t let him in. He said: ‘I am a very proud junkie.’ Hahahaha! I said: ‘Dad, they’re only doing this so you can have a place to sleep.’ He goes: ‘Fuck that, I’m not an alcoholic, I’m a junkie.’”

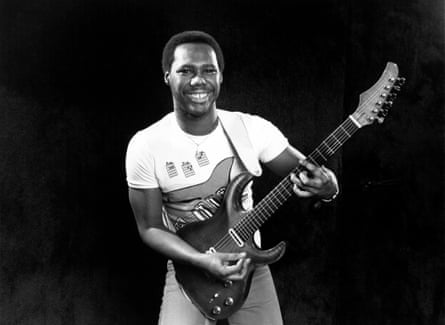

Today, we feel a long way from the Lower East Side of his childhood. We meet at the Serpentine Gallery in London, which is hosting its annual summer party. Shrubs are being pruned into “2018” topiary, champagne flutes lined up and an impromptu dance-floor laid out. Chic will play a private gig for London’s rich and famous – supermodels, actors and the odd politician-turned-newspaper editor. Rodgers is wearing a red velvet jacket, red trousers with more zips than stitches, a silver choker that a pitbull would be proud to own, and a black beret. Few people could get away with it. But Rodgers, recently found to be clear of cancer for the second time, looks wonderful; from behind, with his tiny bottom and stick-like legs, he could pass for the teenager who studied classical music at school. Initially, Rodgers thought he would be a percussionist like Nile senior. But the school orchestra needed a flautist. He then moved to the B-flat clarinet, before discovering jazz guitar. Not surprisingly, Rodgers was a precocious youngster. By 13, he was sniffing glue, and by 15 he was sleeping in subways and had contracted gonorrhea. He rarely slept (at the convalescent home, the abuser stalked the dormitory in the dark, and Rodgers learned to sleep between dawn and breakfast – a pattern that stuck). Yet, like his parents, he remained fully functional. He became a session guitarist, touring with the Sesame Street band, before joining the house band at Harlem’s Apollo theatre, backing the likes of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Aretha Franklin. At 17, he met bass player Bernard Edwards. Rodgers was a bell-bottomed revolutionary hippy, Edwards a clean-living conservative young man. They became inseparable – and musical life partners.

Rodgers also became a member of the Harlem chapter of the Black Panther party. “I was section leader of the Panthers. I moved up in rank rather quickly because I was a martial artist,” he says. What he loved about the Panthers was that new members were given responsibility immediately, to test them. “The day I became a Panther, I had to stand security for Sister Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X’s widow. Very first day!” Was he armed? “No. Just martial arts.”

Last year, Rodgers helped out in the aftermath of the fire at Grenfell Tower in London. He says it reminded him of his Panther days – young people taking the lead, transforming the community. “It was like going back to the streets. To sort out clothes, to feed people, to make sandwiches, to make drinks, to carry stuff, that’s easy. Man, those kids were so damn inspirational.”

What was his hope for the US when he was a Panther? “I thought America would become this beautiful utopian place. Of course, it never happened. The closest thing that ever happened to it was disco! Period. End of story.”

Rodgers has an astonishing mind, racing between stories. Within seconds, we lurch from the Panthers to the ghettoisation of Los Angeles (where his family moved), the manicured lawns of Compton, and America as a nation built on slavery.

What does he think about Kanye West’s suggestion that slavery was a “choice”? He blows a raspberry. “Come on! Slavery a choice?” He gives it more thought. “As a human being, I always used to think there were always more slaves than slave owners. Why were we so afraid of guns? Why didn’t we just take over?” So, he has sympathy with what West said? “No, not at all. Let me take you back to my own childhood. There were a hell of a lot more kids in that room than the one guy who was the abuser. At any point, the 20 or 30 kids could have rebelled. But this person represented an authority figure. He seemed more powerful by himself than all the kids collectively. So, it’s psychological warfare.” Is what West said dangerous? “I can’t really tell. I don’t know how seriously people take entertainers nowadays.”

Which brings him to Trump. “The first time I met him, I couldn’t believe what came out of his mouth. I was doing The Merv Griffin Show, and Merv Griffin has to be the nicest person you will ever meet. It was myself, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Donald Trump.” Before the show, Trump boasted to the two of them that he had whupped Griffin in a property deal. “He was talking about Merv Griffin in such a derogatory way, talking about how stupid he was, and we’re going: ‘Do you think we’re going to think, “Oh wow, that guy’s a really smart businessman, he must be the smartest guy in the world.” We’re not thinking that. We’re thinking: ‘If you believe you took advantage of Merv Griffin, you should not be bragging about that because he’s the nicest guy in the world. You should feel like a jerk and should shut the hell up.’”

Has he met Trump since? “Go on the internet. You’ll see him taking pictures with me all over the place. He was that kind of guy. He used to take pictures with anybody who was happening in the 70s and 80s, and then he’d call the press ... At the time, I was going out with the crown princess of Yugoslavia so you’d see tonnes of pictures of him behind me.” He pauses. “He’s a builder, but I bet you he doesn’t even understand junior high school geometry. I bet you if I talked to him about Non-Euclidean geometry he’d look at me like: who’s Euclid? Hahahaha!”

Rodgers seems to measure out his life in girlfriends. He has been with his current partner, former magazine editor Nancy Hunt, for more than 20 years. Like him, she didn’t want children. Rodgers has said he spent too much of his life looking after his own family, changing his younger brothers’ nappies, to rear his own.

It’s time for the soundcheck. As he heads to the stage, Paul McCartney strolls past with his wife, Nancy Shevell. He spots Rodgers. It is obvious he and Shevell are fans. McCartney hugs Rodgers, while Shevell gets out her iPhone to take a photo of them together. “Sorry,” she says. “I wouldn’t normally do this.”

Rodgers has changed into an all-black outfit. Later, for the gig, he is all in white – every inch the rock star. Funny thing is, he never was one really. Chic were never about individuals, they were an ensemble. Rodgers and Edwards were the only permanent members. The rest were hired hands, albeit brilliant hired hands (notably Luther Vandross before his solo success). The groove was propelled by Edwards’ driving, repetitive bass. As for Rodgers, he never bothered with showy solos. He played quietly, rhythmically, cerebrally – more like a technician than a frontman.

Rodgers has always considered himself a composer and organiser rather than a star. “I didn’t have to be the best performer, I had to be a terrific composer. Duke Ellington cannot play like Art Tatum, right? But Duke Ellington is the guy who makes the plans, the general; Art Tatum is the guy who’s going to get all the medals across his chest. So, I became Duke Ellington. I was the guy who made the plan.”

Chic are an extraordinarily tight, funky unit. Their songs are impossible not to move to (Le Freak, I Want Your Love, Dance, Dance, Dance, Good Times). Rodgers and Edwards also wrote the classic disco anthems We Are Family and Lost in Music for Sister Sledge. Yet there were so many other influences at play beyond disco – classical, glam rock, jazz, prog rock, soul. They were possibly more influential after their heyday, often sampled by hip-hop artists – most famously Good Times on Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight.

No band represented the hedonistic 70s quite like Chic. This was before Aids and punk rock. Life seemed simple for young people – sex, drugs and disco. One image summed up the era: Bianca Jagger on a white horse at Studio 54, where owner Steve Rubell handpicked his guests from the beautiful people queuing outside. After Rodgers and Edwards were turned away from the club, they wrote a song about it that went “Aaaah, Fuck off!” It morphed into “Aaaah, Freak out” on Le Freak, which came out in 1978 and topped the Billboard charts for seven weeks. By the next year, it was all over. On 12 July 1979, at a baseball promotion at Comiskey Park, Chicago, a crate of disco records was blown up on the field between games. Disco was dead – long live punk. Chic’s Good Times reached No 1 a month later, but that was their last US hit, and Rodgers briefly became persona non grata.

He soon re-emerged as the producer with the midas touch. There was Diana Ross’s album Diana (her biggest seller), followed by David Bowie’s Let’s Dance (his biggest seller), and Madonna’s Like a Virgin (which sold 21m copies). As usual, at the Serpentine gig, he plays non-Chic hits he has either produced (Let’s Dance) or co-written (Daft Punk’s Get Lucky). He also plays Chic’s new single, the catchy Till the World Falls. It’s a taster for the band’s first new album in 25 years, which will be released in September.

You must be excited, I say, coming back after all this time. He gives me a look, and says the band has never been away; they were always touring, playing his music, and for him that was the main thing. He reminds me that Chic was never a regular band. Until Edwards died, aged 43, in 1996, Chic was the two of them plus extras, and today it is just Rodgers plus extras. “Chic has always been the best musicians I could find who were available at the time. That may sound cold, but it’s actually very warm – it’s the best muscians I could find. Turn over any Chic album and look at who’s playing on our records, the New York Philharmonic, all the best musicians in the world.”

Soundcheck over, Rodgers is in a car heading back to his hotel. I ask if he meant it when he said disco was the closest the US got to utopia. He lights up. “Totally. When I walked into a nightclub with my girlfriend, I was a total jazz snob, and she worked at a jazz club. We were maybe 23, and I heard Donna Summer singing Love to Love You Baby and I heard Eddie Kendricks’ Girl You Need a Change of Mind, and I saw gay people dancing with straight people and black people and white people and Asian people and Latino people, and I saw they were doing this dance called the Hustle and everybody seemed to know how to do it. And me and my girlfriend imitated people doing it and nobody made fun of us. I was like, whoa! Because even at the height of the political 60s and early 70s, no matter how much we tried to say it was about peace and love, people would make fun of you if you didn’t fit in.”

When Rodgers was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010, he was told it was aggressive. Is he surprised to still be around? “Extremely. I’m not surprised to be around because of surviving cancer, I’m surprised to be around because the slang on the street was never trust anyone over 35. We lived a live-fast, die-young lifestyle, and that is indicative of the huge amount of people I have lost that were in my world.”

Drugs and drink almost did for Rodgers in 1984. “I died eight times in one night and they brought me back. Eight times my heart stopped. I was hanging out with Robert Downey Jr … It was coke and alcohol. I was fine, but then I passed out. Typical rock’n’roll death … you choke on your own vomit.” He says the doctor was filling out his death form when he decided he wasn’t quite done with life. He has been teetotal and drug-free for 24 years.

So many of Rodgers’ collaborators have died, often unexpectedly. In April, there was the 28-year-old Swedish DJ Avicii. Rodgers co-wrote his hit single Lay Me Down, and has described Avicii as “the best natural melody writer in my life”. In 2016, Bowie died of cancer. Rodgers has cited their work on Let’s Dance as his most important collaboration because it rescued both their careers. He has called Bowie “the Picasso of rock‘n’roll”, but today he is thinking about him in a different way. “I never met a person who was so the antithesis of a racist,” he says. Is that unusual in the music industry? “Highly.”

Is it true the new Chic album features a song dedicated to Prince? He shakes his head. “I took that song off. I had written a song called Prince Said It. Prince and I had been friends for such a long time, and he knew that I started out as a jazz guitar player and that I still only practise playing jazz. He always said to me: put out a jazz album. So, I was going to put out this song that was super jazzy and the chorus was going to have the whole band stop and go ‘Prince said it’ just like his song that went ‘You sexy mother fucker’. Then after Prince passed away, it felt inappropriate. It felt as if I would be captalising on his death. It just felt wrong to me.”

As for Edwards, Rodgers calls him “the best musician I have ever seen in my life”. Would they still be playing together if he were alive? “Of course. Bernard died on stage with me.” He stops to clarify. “He passed out on stage and we revived him and he continued playing the show, which surprised the hell out of me. I didn’t even know he had passed out. He died later in his room. If you look at the last interview with Bernard and me, he says there is no one in the world I like playing with more than Nile. He’s my guitar player and I’m his bass player. That always makes me cry.” He repeats it quietly as if to himself. “He’s my guitar player and I’m his bass player.”

It would be easy for Rodgers to get melancholy about losing so many friends. But he doesn’t. Instead, he imagines they are still here. “I love how I talk about people in the present tense even though they have been dead for a long time. I still feel I could walk down the street and Bernard is walking with me. I still think about Luther Vandross in the present tense. The other day someone was asking me about music that makes me cry and I said: ‘Every time I go and see Luther and he sings A House Is Not a Home.’ Of course you can’t go and see Luther any more and hear him sing that, but I still think I can.”

We are almost at his hotel, and he is thinking about the band he played with as a teenager that opened for the Stooges and Jeff Beck. “They were smokin.” He smiles a lovely boyish smile. “I have never had a bad band. Nobody has ever seen Nile Rodgers in a bad band. EVER.” And the best band he’s played with? He looks at me as if I’m daft. “Chic.” Any particular lineup? “No. Just Chic. They always get better.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion