In the Soviet Union, desk drawers became sarcophagi; entombed within them were the creative endeavours of the most talented and perceptive Soviet citizens. Yet it is best not to idealise such hiding spaces as reserves of dormant illumination; indeed, there may have been no limit to the depths of darkness possible within them.

Consider the case of Danzig Baldaev. Born in 1925 in Ulan-Ude, in east-central Russia, Baldaev was the son of an ethnographer who was arrested as an "enemy of the people". He grew up in an orphanage for the children of "enemies" and following his service in the second world war was "forced", as he described it, by the NKVD (a forerunner of the KGB) to work as a warder at Kresty prison in Leningrad, now St Petersburg. His employment in the Soviet penal system took him all over the USSR, but in private, he poured the psychological detritus of his profession into a terrifying work of sadistic pornography, which he dedicated, in 1988, to Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Baldaev was not a pornographer in any conventional sense, but was nevertheless inundated by pornography, for he was surrounded by the pornographic sadism that characterised – sometimes by design, sometimes by default – the Soviet punitive machine. An amateur anthropologist who had been denied an education because of his family's political ignominy, Baldaev struggled to anatomise on paper the system that defined him, and in which he was complicit.

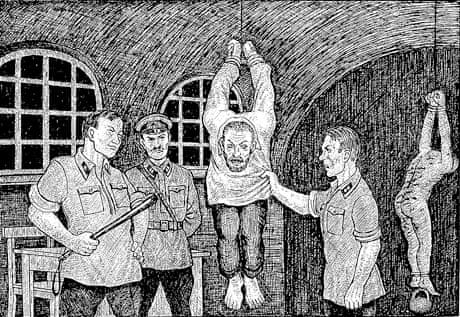

His drawings and descriptions imprint themselves awfully in the imagination: in one image, three nude, emaciated women, so wasted by hunger and work that their uteruses have prolapsed, line up before a camp doctor beneath a sign bearing Lenin's dictate, "He who does not work, neither shall he eat." In another, an unclothed university professor is lashed, sodomised and gloated over by his uneducated guards for his pursuit of an unapproved science. Elsewhere, sick workers are steamed in a sauna, and then hauled naked into temperatures below freezing to expire from shock. On the most nauseating page, a young woman who has refused the sexual advances of her captors sits tied to a tree atop an anthill in the notoriously insect-ridden Siberian woods with a tube "inserted into the vagina so the ants could crawl inside".

Readers may wonder whether Baldaev's illustrations are accurate documents of atrocities at all, or were intended as anti-Soviet polemic. The answer is both: Baldaev depicts the Bolshevik coup of 1917 as a national tragedy following which "the peoples of Russia recalled life under the tsar as a lost paradise". He describes the Bolsheviks' antireligious militancy as the sole impetus for the moral collapse he encountered. Yet while his analysis of the Soviet disaster rests upon simplistic nostalgia for a golden age of church and monarchy, the editors of this book have convincingly corroborated many of his representations with parallel accounts from the canon of Russian Gulag literature.

Viewers may also question whether the artistic merits of Baldaev's drawings redeem their potential prurience. While it is necessary to know that "enemies of the people" were subjected to revolting forms of torture and humiliation, one may ask: are the interests of history in any way served by a graphic image of a bound woman with ants crawling into her vagina? There are strong artistic precedents to support Baldaev's case: Goya's Disasters of War, for example, recorded politically motivated atrocities in a similar manner and thus prophesied the modern conception of warfare. Gustave Doré's macabre and meticulous engravings for each layer of hell in Dante's inferno gave to posterity a necessary encouragement to contemplate the inverse side of heaven. Baldaev's drawings resemble both artists' works.

Yet they are not the work of a passive witness, nor are they products of the imagination. They are good art, but they bear the taint of his choice between authority and victimhood. While it would be naive to judge him from a position of safety and comfort, Baldaev dared only to hate the system and bear witness to it; he did not, as the intrepid Solzhenitsyn did, risk confronting it. The terrible truth he identified – that for many of its servile intermediaries, the Gulag had its contemptible pleasures – was one that could never justly remain buried. It is scarcely surprising that Baldaev longed for the old church, for the bottom drawer must have made a poor confessional. While his drawings may have unburdened him a little, his lengthy private lingerings over their horrors must also have enervated him, and have helped his superiors to secure his submission.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion