Czech riot police beat protesters: 50,000 call for freedom and end to Communist rule

by Michael Simmons in Prague

18 November 1989

Police and troops used batons to break up a march last night through central Prague by 50,000 people demanding an end to Communist rule.

The biggest anti-government protest in Czechoslovakia for 20 years disintegrated under the batons of riot police and paratroopers after the leadership vowed again to resist the changes surging through Eastern Europe.

Witnesses saw at least 100 people detained. Some were badly hurt when the security forces – some with unmuzzled dogs – beat hundreds of demonstrators at the head of the column trying to reach Wenceslas Square, the traditional site for demonstrations. Thirteen were admitted to hospital.

‘Dialogue! Dialogue!’, ‘We don’t want the Communist Party,’ ‘Forty years are enough!’ the demonstrators shouted.

Most of the marchers were students. They carried national flags or banners proclaiming ‘Freedom!’ and ‘Stop Beating Students!’

Because the march was organised partly by the Socialist Youth Union – it was called to mark the 50th anniversary of Nazi oppression - the authorities gave official approval, provided it avoided the city centre.

At first police stood aside. But from the cemetery where national heroes are buried the column turned for the city centre, growing as people who had watched it on television joined in. As the marchers streamed along the bank of the River Vltava towards Wenceslas Square the security forces waded into the column and the demonstrators began to flee.

As the protest began the Czechoslovak Communist ideology chief, Mr Jan Fojtik, said in Moscow: ‘I’m certain we can establish a dialogue with reasonable people, but there can be no dialogue with those who set out to destroy our society.’

Mr Fojtik said he foresaw few significant changes and expected Mr Jakes to remain in power in the run-up to a Communist Party Congress in May. But he added: ‘Anything could happen. Life is so stormy at the moment.’

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

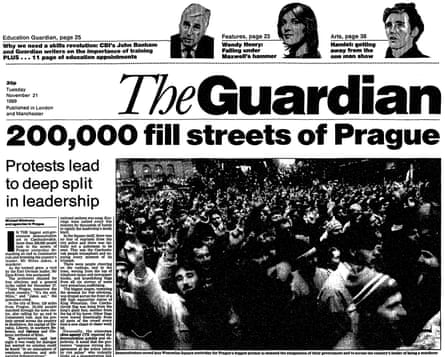

200,000 fill streets of Prague: protests lead to deep split in leadership

by Michael Simmons in Prague

21 November 1989

In the biggest anti-government demonstration yet in Czechoslovakia, more than 200,000 people took to the streets of Prague yesterday demanding an end to Communist rule and branding the country’s leader, Mr Milos Jakes, a murderer.

As the turmoil grew, a visit by the East German leader, Mr Egon Krenz, was postponed.

The protesters shouted for free elections and a general strike called for November 27. ‘Today Prague, tomorrow the whole country,’ ‘It’s the end, Milos,’ and ‘Jakes out,’ the protesters cried.

In the city of Brno, 120 miles from Prague, 30,000 people marched through the town centre, also calling for an end to Communist rule. And the protests spread across the country to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, Liberec, in northern Bohemia, and Ostrava and Olomouc northeast of Brno.

The government said last night it was ready for dialogue but warned no solution could be found ‘in an atmosphere of emotions, passions and anti-socialist demonstrations’.

Wenceslas Square, a wide boulevard about the same length and breadth as Whitehall, London, was filled to overflowing with a crowd which was much more assertive, but never aggressive, than any in the last four days and it was unanimous in its contempt for the country’s leadership.

As party slogans and Communist stars were covered with the national flag great cheers went up, and as a home-made slogan proclaiming that ‘truth will prevail’ was raised, the national anthem was sung. Key-rings were rattled every few minutes by thousands of hands to signify the leadership’s death knell.

In the Square itself, there was no fear of reprisals from the riot police and there was initially not a policeman to be seen. This was the Czechoslovak people triumphant and enjoying every moment of its triumph.

There were people cheering on the rooftops, and in the trees, waving from the top of telephone boxes and newspaper kiosks, and brandishing flags from all six storeys of some very precarious scaffolding.

The biggest slogan, repeating the demand for free elections, was draped across the front of a 50ft high equestrian statue of King Wenceslas. One Czechoslovak flag was hung from the king’s giant foot, another from the leg of his horse. Other flags were waved frenetically from all parts of the crowd every time a new chant or cheer went up.

Unusually, the state-run news agency CTK reported the demonstration quickly and objectively. It noted that the protesters ‘express strong disagreement at the action taken by riot police’ who violently broke up a demonstration last Friday.

Throughout the city, students were on strike, theatres were on strike, shops were closed and offices deserted.

At one point the cry went up for Mr Ladislav Adamec, the seemingly reformist Prime Minister, to come and speak to the crowd. Mr Vaclav Havel, who has emerged as the moral leader of the opposition, disclosed yesterday that Mr Adamec has in fact been putting out feelers to talk with the opposition.

It is clear now that the Czechoslovak leadership is deeply split, with Mr Adamec leading a conciliatory group while Mr Jakes and the Prague leader, Mr Miroslav Stepan, cling to a hard line.

Mr Havel, who held a press conference in his riverside flat unimpeded by the security forces, said yesterday that ‘the ideals for which I have been struggling for many years and for which I have been imprisoned are beginning to come to life as an expression of the will of the people’. He announced the formation of the Civic Forum, clearly based on the resilient success of East Germany’s New Forum. It was he said, ‘an association open to all who wanted democracy in Czechoslovakia‘.

It demands the removal of all politburo members ‘responsible for the devastation’ which followed the 1968 invasion; the establishment of a commission including Civic Forum members, to look into last Friday’s violence; and the release of all prisoners of conscience. Asked whether he saw himself as Czechoslovakia‘s future leader – no longer a preposterous question by any means – he replied: ‘I would rather be a kingmaker than a king.’

Mr Havel said coal miners in northern Bohemia had sent him a message that they were going on strike from yesterday and were urging others to join in. It would be the first such action to back political demands since 1968.

Prague’s people dance in the streets

25 November 1989

Vera Handlikova is 66 and cried all night when she saw the tanks come into Wenceslas Square in 1968. Last night she was there again and crying again. ‘It’s perfect,’ she said. ‘It’s marvellous.’ It was too late to buy a drink, but the square was full of people drunk with joy. Soldiers in uniform, mad slogans pinned to their backs, walked up and down, arm in arm, waving flags.

Czechs scrap one-party rule

by Michael Simmons and Jon Bloomfield in Prague

29 November 1989

The Czechoslovak government yesterday bowed to overwhelming people’s power and agreed to the opposition’s key demand for an end to one-party rule.

The announcement came at the end of a third round of negotiations between the Prime Minister, Mr Ladislav Adamec, and the opposition Civic Forum movement. It followed 11 days of massive demonstrations and a general strike on Monday.

‘The premier of the federal government promises that by December 3, 1989, he will propose to the president of the republic the appointment of a new government,’ said the Minister without Portfolio, Mr Marian Calfa, after the two-hour talks. ‘This government should be based on a broad coalition representing non-party members, other political parties and naturally the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.’

The government will also propose to the country’s Federal Assembly sweeping reforms of the constitution, including dropping the clause which guarantees the leading role of the Communist Party, said the announcement.

It will also urge the removal of the constitutional requirement to base the education system on Marxism-Leninism. ‘This concept will be replaced by a concept of education based on scientific knowledge and the principles of humanitarianism,’ said Mr Calfa.

The government also announced that, less than 10 days after the Civic Forum was born, it has been officially recognised. Permanent premises would be found for it. In its short life so far the Forum has been restricted to a variety of inadequate and obviously temporary premises, ranging from the flat of Mr Vaclav Havel, the playwright, to a magic lantern theatre.

Tributes greet President Havel

by Michael Simmons

30 December 1989

To trumpeted fanfares, standing ovations and cheers from the people, and a 20-gun salute, Vaclav Havel, playwright extraordinary and leader of the year’s most peaceful revolution against Stalinism, was acclaimed in Prague Castle yesterday as Czechoslovakia‘s new President.

The ceremony was in the hands of Mr Alexander Dubcek, who came in from the political cold less than 24 hours before, to be elected head of the new-style Federal Assembly. He it was who ushered in the new head of state to the dais in Prague Castle where the oath was sworn. Every member of Mr Dubcek’s Assembly had voted that Mr Havel should be the country’s first non-Communist leader since 1948.

It is a post that Mr Havel did not seek but for which he was the only serious candidate. Three out of every four of the population, according to a recent poll, supported him. Now, he says he will keep the post until free elections are held, probably in the first half of the coming year.

As a Central European intellectual, his credentials are impeccable. Only a few months ago, he was in prison for ‘subversion’ and ‘anti-state activities’; but yesterday, before the day was out, he was being congratulated as a worthy successor to the country’s first leader, Tomas Garrigue Masaryk.

Nominating him, the Prime Minister, Mr Marian Calfa, declared: ‘Although he has been forced to live on the fringe of society, he has retained his moral integrity.’

It was a tribute which will mean as much to Mr Havel as any formal honour. After the vote, which had been taken in the Vladislav Chamber, where the Kings of Bohemia were once crowned, Mr Havel was sworn in. ‘I swear on my honour and conscience, my loyalty to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic,’ he said.

The word ‘Socialist’ in this context could also become an anachronism very soon. Civic Forum wants just the ‘Czechoslovak Republic’ to be enshrined in the new Constitution; the promise ‘to serve the cause of socialism’ was deleted from the presidential oath on Thursday of this week.

On leaving the castle, the dapper-suited President Havel, more at home in sweater and jeans, stood with everyone else for a rendering of the national anthem. This was the theme tune at last month’s revolutionary rallies, where the crowds sang it with great gusto and clapped to the jaunty rhythm of its concluding lines.

Editorial: Fine lines in a true drama

3 January 1990

So a Czechoslovak playwright is not just an unacknowledged legislator in his world but the possessor of full presidential authority – a fitting start to the 1990s. Mr Vaclav Havel speaks with immense moral authority in the name of the Czechoslovak state. In the space of two days he outlines his country’s future and meditates in public on the German question. He makes it sound very different from the usual sort of presidential utterance, and so he should. Just a few months ago he was warning that words were double-edged weapons, mightier than ten military divisions in their ability to change history. Now he has to pronounce them – a much more difficult affair.

The commentators have seized on the symbolism of Mr Havel choosing to pay his first foreign visit to the Germanys and not to the Soviet Union. But it is natural for the new government in Prague to tackle head-on its relationship with the state whose historical influence so powerfully preceded that of the Red Army. The notion that Czechoslovakia‘s natural home lies westwards in a modern Europe has been central to the new thinking of the Civic Forum. The Czechoslovak Communist Party, too, in its reformed programme, stresses the country’s need to take its ‘worthy place’ in a new European home.

‘Europe need have no fear of a democratic Germany. It can be as large as it wants,’ said Mr Havel yesterday in East Berlin. This is certainly a different way of using words, which one cannot imagine coming from the lips of any British or French politician. Perhaps those who have been denied democracy for so long are a shade too ready to attribute magical powers to it. But the essential thrust of the argument is refreshingly straight-forward: If the only good Germany is a democratic Germany, then we should have enough vision to disregard the chill contingencies spelt out on the geopolitical map.

Before he left for Germany, Mr Havel had delivered a presidential address which could not have diverged more sharply from the usual practice of telling the nation that everything was fine in the best of socialist worlds. The only doubt must be whether he has painted instead a picture so uncompromisingly black that it could weaken rather than encourage the national unity which he seeks to construct. The old regime, he said, had turned a gifted people into ‘little screws in a monstrously big, rattling and stinking machine.’ Yet it was a regime which the people had largely inflicted upon themselves. If it is true that in the process they had become, in his words again, ‘morally sick,’ then the rebirth of the last few weeks shows how quickly the disease can be cured.

Whether this national revival can be maintained will depend before long upon the hard grinding out of coherent policies which Mr Havel only sketched with the broadest sweep of his playwright’s pen. He pledged all his authority and influence to have ‘free elections soon and in a dignified way.’ That could be the easiest part. He went on to declare that Czechoslovakia‘s strategical goal is ‘to prepare the transition to a market economy.’ This is the real unchartered territory. Socialism, Mr Havel wrote last year, has long ago become no more than an ‘incantation.’ But the complex problems of state and society may not automatically be solved by invoking another concept which mixes reality with myth.