common comfrey Symphytum officinale L. - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

common comfrey Symphytum officinale L. - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

common comfrey Symphytum officinale L. - Alaska Natural Heritage ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong><br />

<strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong> L.<br />

Synonyms: <strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong> ssp. uliginosum (Kern.) Nyman, <strong>Symphytum</strong> uliginosum Kern.<br />

Other <strong>common</strong> names: asses-ears, backwort, boneset, bruisewort, consolida, consound, gum plant, knitback, knit-bone,<br />

slippery-root<br />

Family: Boraginaceae<br />

Invasiveness Rank: 48 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological<br />

attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a<br />

plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native<br />

ecosystems.<br />

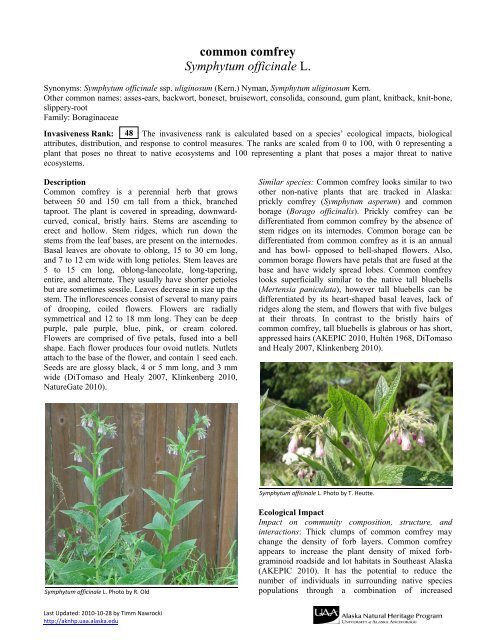

Description<br />

Common <strong>comfrey</strong> is a perennial herb that grows<br />

between 50 and 150 cm tall from a thick, branched<br />

taproot. The plant is covered in spreading, downwardcurved,<br />

conical, bristly hairs. Stems are ascending to<br />

erect and hollow. Stem ridges, which run down the<br />

stems from the leaf bases, are present on the internodes.<br />

Basal leaves are obovate to oblong, 15 to 30 cm long,<br />

and 7 to 12 cm wide with long petioles. Stem leaves are<br />

5 to 15 cm long, oblong-lanceolate, long-tapering,<br />

entire, and alternate. They usually have shorter petioles<br />

but are sometimes sessile. Leaves decrease in size up the<br />

stem. The inflorescences consist of several to many pairs<br />

of drooping, coiled flowers. Flowers are radially<br />

symmetrical and 12 to 18 mm long. They can be deep<br />

purple, pale purple, blue, pink, or cream colored.<br />

Flowers are comprised of five petals, fused into a bell<br />

shape. Each flower produces four ovoid nutlets. Nutlets<br />

attach to the base of the flower, and contain 1 seed each.<br />

Seeds are are glossy black, 4 or 5 mm long, and 3 mm<br />

wide (DiTomaso and Healy 2007, Klinkenberg 2010,<br />

NatureGate 2010).<br />

Similar species: Common <strong>comfrey</strong> looks similar to two<br />

other non-native plants that are tracked in <strong>Alaska</strong>:<br />

prickly <strong>comfrey</strong> (<strong>Symphytum</strong> asperum) and <strong>common</strong><br />

borage (Borago officinalis). Prickly <strong>comfrey</strong> can be<br />

differentiated from <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> by the absence of<br />

stem ridges on its internodes. Common borage can be<br />

differentiated from <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> as it is an annual<br />

and has bowl- opposed to bell-shaped flowers. Also,<br />

<strong>common</strong> borage flowers have petals that are fused at the<br />

base and have widely spread lobes. Common <strong>comfrey</strong><br />

looks superficially similar to the native tall bluebells<br />

(Mertensia paniculata), however tall bluebells can be<br />

differentiated by its heart-shaped basal leaves, lack of<br />

ridges along the stem, and flowers that with five bulges<br />

at their throats. In contrast to the bristly hairs of<br />

<strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong>, tall bluebells is glabrous or has short,<br />

appressed hairs (AKEPIC 2010, Hultén 1968, DiTomaso<br />

and Healy 2007, Klinkenberg 2010).<br />

<strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong> L. Photo by T. Heutte.<br />

<strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong> L. Photo by R. Old<br />

Ecological Impact<br />

Impact on community composition, structure, and<br />

interactions: Thick clumps of <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> may<br />

change the density of forb layers. Common <strong>comfrey</strong><br />

appears to increase the plant density of mixed forbgraminoid<br />

roadside and lot habitats in Southeast <strong>Alaska</strong><br />

(AKEPIC 2010). It has the potential to reduce the<br />

number of individuals in surrounding native species<br />

populations through a combination of increased<br />

Last Updated: 2010-10-28 by Timm Nawrocki<br />

http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

competition for space, nutrients, water, bees and other<br />

pollinating insects, and seed dispersal agents such as<br />

ants (DiTomaso and Healy 2007, Goulson et al. 1998,<br />

Peters et al. 2003). It contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids<br />

that can cause liver damage in herbivores, resulting in<br />

death if enough alkaloids are consumed (DiTomaso and<br />

Healy 2007, Medicinal Plants for Livestock 2008). The<br />

seeds of <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> are very attractive to ants in<br />

Germany (Peters et al. 2003), and they may alter antplant<br />

interactions in <strong>Alaska</strong>. The flowers are pollinated<br />

by insects, especially long-tongued bees (DiTomaso and<br />

Healy 2007, Goulson et al. 1998). Native plantpollinator<br />

relationships could be impacted by the<br />

presence of <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong>.<br />

Impact on ecosystem processes: Specific ecosystem<br />

impacts caused by <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> are largely<br />

unknown. While this species may reduce the nutrients<br />

and moisture available for native species, it is unlikely<br />

to have any major impacts on ecosystem processes.<br />

Biology and Invasive Potential<br />

Reproductive potential: Common <strong>comfrey</strong> reproduces<br />

by seed and vegetatively from root fragments. Each<br />

flower produces four seeds, and plants are capable of<br />

producing large numbers of flowers (DiTomaso and<br />

Healy 2007). Seeds remain viable in soil for several<br />

years although the exact amount of time is unknown<br />

(Crop Compendium 2010).<br />

Role of disturbance in establishment: Common <strong>comfrey</strong><br />

requires moist, nutrient-rich soil in a disturbed area or<br />

garden (DiTomaso and Healy 2007).<br />

Potential for long-distance dispersal: Seeds are<br />

dispersed by ants (Peters et al. 2003) and water<br />

(Moggridge et al. 2009). The seeds have elaiosomes,<br />

fleshy-oily protuberances that attract ants (Pemberton<br />

and Irving 1990). Common <strong>comfrey</strong> has spread by seed<br />

in Southeast <strong>Alaska</strong> from planted populations (Rapp<br />

2006).<br />

Potential to be spread by human activity: Common<br />

<strong>comfrey</strong> is planted by people in <strong>Alaska</strong> as an ornamental<br />

and a medicinal plant. Planted populations in Glacier<br />

Bay National Park have caused several infestations in<br />

surrounding areas (Rapp 2006).<br />

Germination requirements: Seeds germinate rapidly in<br />

moist soils of open sites. They germinate especially well<br />

in gardens, peat and loam. They are also able to<br />

germinate in water (DiTomaso and Healy 2007).<br />

Growth requirements: Common <strong>comfrey</strong> usually grows<br />

on moist, nutrient-rich soils. In regions with cold<br />

winters, the foliage dies during the winter and<br />

regenerates from the roots with the return of warm<br />

weather. It can tolerate semi-shade (DiTomaso and<br />

Healy 2007, Plants for a Future 2010).<br />

Congeneric weeds: Prickly <strong>comfrey</strong> (<strong>Symphytum</strong><br />

asperum) is a tracked non-native plant in <strong>Alaska</strong> and it<br />

is considered noxious in California (AKEPIC 2010,<br />

USDA 2010).<br />

Legal Listings<br />

Has not been declared noxious<br />

Listed noxious in <strong>Alaska</strong><br />

Listed noxious by other states<br />

Federal noxious weed<br />

Listed noxious in Canada or other countries (QC)<br />

Distribution and Abundance<br />

Common <strong>comfrey</strong> grows on moist, fertile soils in<br />

disturbed areas or gardens (DiTomaso and Healy 2007).<br />

In England, it grows especially well in riparian<br />

environments (Goulson et al. 1998, Moggridge et al.<br />

2009). However, it is not documented as being invasive<br />

in riparian environments in the U.S., nor has it invaded<br />

any riparian environments in <strong>Alaska</strong> (AKEPIC 2010,<br />

DiTomaso and Healy 2007).<br />

Native and current distribution: Common <strong>comfrey</strong> is<br />

native to Europe and was introduced to North America<br />

as an ornamental and a medicinal herb. It can now be<br />

found in Europe, North America, Japan, and Australia.<br />

Infestations are documented from Southeast <strong>Alaska</strong><br />

(AKEPIC 2010, DiTomaso and Healy 2007, Ibaraki<br />

Nature Museum 2010, National Herbarium of South<br />

Wales 2010). It is not known from arctic or subarctic<br />

regions.<br />

Pacific Maritime<br />

Interior- Boreal<br />

Arctic-Alpine<br />

Collection Site<br />

Distribution of <strong>common</strong> <strong>comfrey</strong> in <strong>Alaska</strong><br />

Management<br />

Common <strong>comfrey</strong> can be difficult to remove due to the<br />

potential for vegetative regeneration from root<br />

fragments. Digging is required to remove the plant and<br />

the large network of roots. Populations in Glacier Bay<br />

National Park persisted after multiple years of manual<br />

removal efforts. Mowing plants before they produce<br />

seeds can prevent populations from spreading<br />

(DiTomaso and Healy 2007, Rapp 2006).<br />

Last Updated: 2010-10-28 by Timm Nawrocki<br />

http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu

References:<br />

AKEPIC database. <strong>Alaska</strong> Exotic Plant Information<br />

Clearinghouse Database. 2010. Available:<br />

http://akweeds.uaa.alaska.edu/<br />

Crop Compendium. 2010. Bayer CropScience AG,<br />

Bayer. Available at<br />

http://compendium.bayercropscience.com<br />

DiTomaso, J., and E. Healy. 2007. Weeds of California<br />

and Other Western States. Vol. 1. University of<br />

California Agriculture and <strong>Natural</strong> Resources<br />

Communication Services, Oakland, CA. 834 p.<br />

Goulson, D., J. Stout, S. Hawson, J. Allen. 1998. Floral<br />

display size in <strong>comfrey</strong>, <strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong><br />

L. (Boraginaceae): relationships with visitation<br />

by three bumblebee species and subsequent<br />

seed set. Oecologia. 113(4). 502-508 p.<br />

Hultén, E. 1968. Flora of <strong>Alaska</strong> and Neighboring<br />

Territories. Stanford University Press, Stanford,<br />

CA. 1008 pp.<br />

Ibaraki Nature Museum, Vascular Plants collection.<br />

2010. Accessed through GBIF (Global<br />

Biodiversity Information Facility) data portal<br />

(http://data.gbif.org/ datasets/resource/8030,<br />

2010-09-15). National Museum of Nature and<br />

Science. Ibaraki, Japan.<br />

Invaders Database System. 2010. University of<br />

Montana. Missoula, MT.<br />

http://invader.dbs.umt.edu/<br />

ITIS. 2010. Integrated Taxonomic Information System.<br />

http://www.itis.gov/<br />

Klinkenberg, B. (Editor) 2010. <strong>Symphytum</strong> <strong>officinale</strong> L.<br />

In: E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants<br />

of British Columbia. Lab for Advanced Spatial<br />

Analysis, Department of Geography, University<br />

of British Columbia. Vancouver, BC. [10<br />

September 2010] Available:<br />

http://www.geog.ubc.ca/<br />

biodiversity/eflora/index.shtml<br />

Medicinal Plants for Livestock. 2008. <strong>Symphytum</strong><br />

<strong>officinale</strong> – <strong>comfrey</strong>. Department of Animal<br />

Science, Cornell University. [15 September<br />

2010]. Available at http://www.ansci.cornell<br />

.edu/plants/medicinal/comf.html<br />

Moggridge, H., A. Gurnell, and J. Mountford. 2009.<br />

Propagule input, transport, and deposition in<br />

riparian environments: the importance of<br />

connectivity for diversity. Journal of Vegetation<br />

Science. 20(3). 465-474 p.<br />

National Herbarium of New South Wales. 2010.<br />

Accessed through New South Wales Flora<br />

Online (http://plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au,<br />

2010-09-15). Royal Botanic Gardens and<br />

Domain Trust. Sydney, Australia.<br />

NatureGate. 2010. Finland Nature and Species.<br />

Helsinki, Finland. [4 October 2010] Available:<br />

http://www.luontoportti.com/ suomi/en/<br />

Pemberton, R. and D. Irving. 1990. Elaiosomes on<br />

Weed Seeds and the Potential for<br />

Myrmecochory in <strong>Natural</strong>ized Plants. Weed<br />

Science. 38(6). 615-619 p.<br />

Peters, M., R. Oberrath, and K. Böhning-Gaese. 2003.<br />

Seed dispersal by ants: are seed preferences<br />

influenced by foraging strategies or historical<br />

constraints Flora – Morphology, Distribution,<br />

and Functional Ecology of Plants. 198(6). 413-<br />

420 p.<br />

Plants for a Future. 2010. [5 October 2004] Available:<br />

http://www.pfaf.org/user/default.aspx<br />

Rapp, W. 2006. Exotic Plant Management in Glacier<br />

Bay National Park and Preserve, Gustavus,<br />

<strong>Alaska</strong>: Summer 2006 Field Season Report.<br />

Exotic Plant Program, Glacier Bay National<br />

Park and Preserve, National Park Service, U.S.<br />

Department of the Interior. Gustavus, AK. 124<br />

p.<br />

USDA. 2010. The PLANTS Database. National Plant<br />

Data Center, <strong>Natural</strong> Resources Conservation<br />

Service, United States Department of<br />

Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.<br />

http://plants.usda.gov<br />

Last Updated: 2010-10-28 by Timm Nawrocki<br />

http://aknhp.uaa.alaska.edu