What Is Shingles?

Jump to: Causes | Symptoms | Pictures | Diagnosis | Treatment | Medications | When to see a doctor | Is it contagious? | Vaccine | How long does it last? | Prevention

Nearly one in three people in the U.S. will get shingles, a painful, blistering rash, at some point in their lifetime. It can strike years or decades after having chickenpox, the itchy, red-pocked childhood ailment caused by the varicella zoster virus that was an uncomfortable rite of passage before the varicella vaccine was added to the lineup of pediatric shots in the U.S. in the mid-1990s. But what is shingles, exactly, and what’s the chickenpox connection?

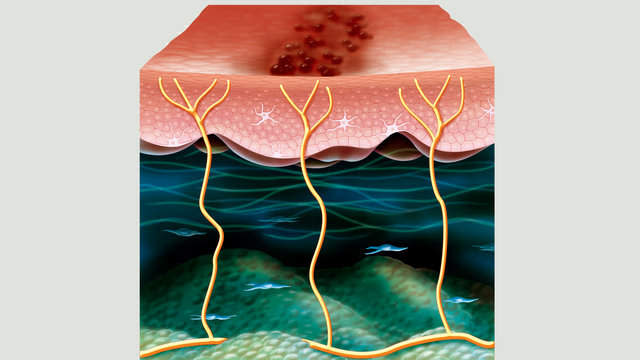

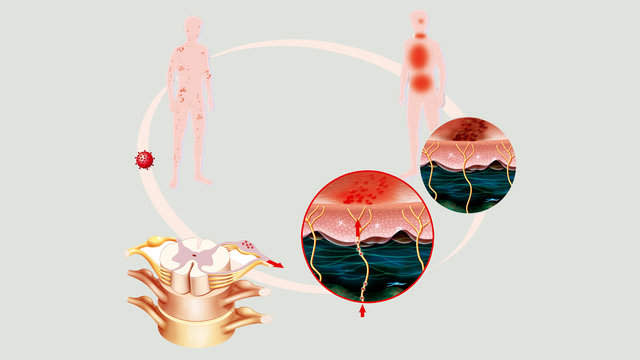

Shingles, also called zoster or herpes zoster, is a viral infection that affects the nerves. It typically produces a painful rash with blisters that can be dangerous in some people. The varicella zoster virus that causes chickenpox is the same one that causes shingles. If you’ve had chickenpox, the virus is lurking in your body, and it can remain inactive for many years. While most adults never get shingles, in others the virus reawakens years later, creating a rash in areas of the skin served by the affected nerves.

An estimated 1 million people in the U.S. have shingles every year. It can occur at any age, but it is much more common in older adults. Most people get shingles only once, but it can make a second or third appearance.

Shingles can be extremely painful. While there is no cure, early treatment can speed recovery, and getting vaccinated can reduce the risk of having shingles or lessen the length and severity of illness if you do get it.

People usually get better in a matter of weeks, with no lasting effects. In rare cases, it can lead to serious complications or even death. Some people experience postherpetic neuralgia, which means they continue to have pain in the area where their rash had been, even weeks, months or years after their skin has healed.

What causes shingles?

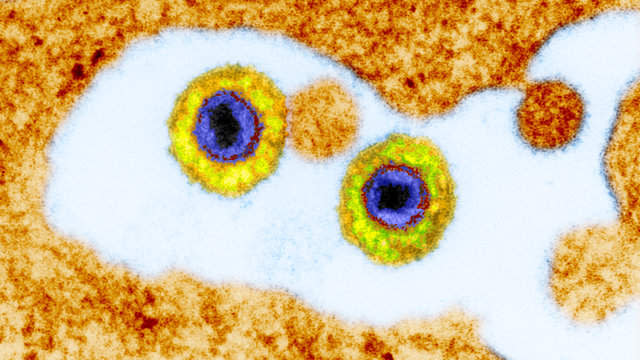

Shingles is caused by the varicella zoster virus. The first time you contract the virus, you get chickenpox. If the virus reawakens in your body later on, it’s shingles.

Varicella zoster is a type of herpes virus, but it is not the same virus that causes cold sores or genital herpes. (Herpes simplex 1, which is transmitted orally, causes cold sores and may cause genital herpes. Herpes simplex 2 is a sexually transmitted infection that causes genital herpes.)

After you’ve had chickenpox, the varicella zoster virus enters the bloodstream, infecting the nerves. The virus can remain dormant, essentially asleep, for years, or it can reawaken, traveling from nerve fibers to the skin surface above—and that’s when shingles symptoms can arise.

Scientists don’t know exactly why some people develop shingles and others don’t, but there are some common risk factors. It tends to flare up in people with weakened immune systems, including HIV and cancer patients, and organ transplant patients who take immune-suppressing medications to prevent organ rejection. Stress or trauma may play a role. Shingles also may be age-related, since it mostly affects older adults, especially people who are 60 to 80 years old.

Symptoms of shingles

Shingles symptoms appear in stages. Initial signs of infection are usually burning, stabbing, or tingling pain; skin sensitivity; or itching across a band of skin, generally on one side of the body. Some people have symptoms of a viral infection, like headache, fever, chills, fatigue, or nausea. A couple days to two weeks later, a red rash of round pocks erupts on the skin’s surface where the pain and itching occurred. Soon after, those dots become fluid-filled blisters that ooze.

“Shingles” comes from the Latin word, cingulum, meaning girdle, while “zoster” (another name for shingles) derives from the Latin and Greek words for girdle. As each name suggests, a band of blisters wraps around one side of the body, like a girdle, often around the waist, chest, stomach, back or buttocks. But it can also appear on one side of the face, around an eye or across the forehead. And it may even invade internal organs. The location of the blisters is related to the nerves affected by the reactivated virus.

The blisters dry out and crust over days or weeks after they first appear. But the skin may be permanently discolored and scarred afterward.

Common symptoms of shingles include:

Burning, stabbing, or tingling pain

Itching

Skin sensitivity

Fever

Chills

Headache

Fatigue

Nausea

Red rash

Fluid-filled blisters

Skin that looks burned

Shingles pictures

Shingles usually appears in a recognizable belt-like or girdle pattern along the left or right side of the body. The shingles rash may cover a wide swath across the waist, chest, stomach, back, breasts, or buttocks, but it rarely wraps all the way around the body.

Shingles can pop up on the face or neck. Sometimes the infection invades other body sites, like an arm or a leg. About 20% of shingles patients have rashes on adjacent skin surfaces that overlap.

Less frequently, the shingles rash is widely disseminated, covering three or more different skin surfaces. This occurs particularly among people with frail or depressed immune systems.

Rare complications of shingles can lead to hearing loss, blindness, and even death.

How is shingles diagnosed?

Doctors diagnose most cases of shingles based on physical signs and symptoms. The tipoff is the distinctive, band-like rash that most people develop. It is usually accompanied by itching, tingling, or pain in an area of the body served by nerves prone to infection during a prior bout with chickenpox.

In some cases, shingles cannot be diagnosed by signs and symptoms alone, especially in people with weak immune systems whose rash strays from the typical girdle-like pattern, or in individuals who may be experiencing complications from other conditions. Some people show up at their doctor’s office having pain or other symptoms before a shingles rash appears. And, in rare instances, a person may have shingles with pain and itching but no rash. In each case, additional testing may be required to pinpoint the exact cause.

A doctor may take a scraping of skin cells for examination under a microscope to determine whether the rash is shingles or something else.

A blood sample may be taken to test for varicella zoster virus DNA. High levels may indicate an active infection.

Blood testing can also detect antibodies to the virus and, depending on the levels, may indicate a first-time case of chickenpox or a previous case that has reactivated, becoming shingles.

Shingles treatment

Once diagnosed with shingles, you will be treated with antiviral medicines. The sooner you start treatment, the better off you will be. Prescription antiviral medicines, including acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir, are not cures for shingles, but these drugs can weaken the virus, reduce pain, expedite healing, and stave off complications. Antiviral medicines are less effective when taken three or more days after a shingles rash has appeared.

Your doctor also may recommend over-the-counter or prescription pain-relief medicines and topical ointments to numb the pain.

People who develop postherpetic neuralgia, or long-term pain after their shingles rash has healed, may be given antidepressants (amitriptyline, for example), anti-seizure drugs (such as gabapentin and pregabalin) and pain relief medicines, including opioid painkillers.

Medications

Acyclovir (Zovirax) – This is the oldest antiviral medication. Zovirax is available as a tablet, capsule, or liquid. A generic version of acyclovir is also available. Acyclovir requires frequent dosing, as often as five times a day for seven to 10 days.

Famciclovir (Famvir) – This antiviral medication was approved for use in 1994. A generic version is available. It is generally taken three times a day for seven days.

Valacyclovir (Valtrex) – Approved in 1995, this antiviral drug comes in tablet form and is available as a generic. The recommended dosing is three times daily for seven days.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil) – These common pain-relief options may help ease mild shingles pain, but may not work if the pain is more severe.

Topical treatments – Products containing capsaicin, an ingredient in hot peppers, or lidocaine, a numbing agent, may help ease shingles pain. There are creams and lotions that contain capsaicin. Lidocaine comes in different forms, including sprays and patches.

Nerve blocks – Injectable numbing medicines may be used when oral medicines fail to provide relief from intense pain.

Antidepressants – Drugs like amitriptyline may be prescribed to shingles patients to alleviate postherpetic neuralgia.

Anticonvulsants – Medicines to prevent seizures, like gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica), are used to treat nerve pain that persists after an episode of shingles.

Opioids – Powerful opioid medications like morphine may be used for a limited period of time to ease severe pain, especially in people with postherpetic neuralgia.

When to see a doctor

This is not the time to watch your symptoms develop and wait for the rash to run its course. Although most cases of shingles resolve in two to six weeks, the risk of longer-term complications rises with age, weakened immunity, and delay or absence of treatment. If you think you have shingles, it’s important to get diagnosed right away. You can see a general practitioner, family medicine physician, internist, dermatologist, or neurologist for an evaluation.

Starting antiviral medications as soon as symptoms arise, within 24 to 72 hours of the first sign of a rash (the earlier, the better), can shorten the duration and severity of your illness and ease the pain of shingles. Early treatment can also reduce the risk of complications. Postherpetic neuralgia, the most common shingles complication, causes persistent pain even after the rash disappears.

Tell your doctor why you think it might be shingles. If a diagnosis cannot be confirmed based on signs and symptoms, he or she can order tests to determine whether you have shingles.

Are shingles contagious?

You cannot catch shingles from other people. You can only get shingles if you’ve had chickenpox before. But is shingles contagious? Yes, people with active cases of shingles are contagious: They can give other people chickenpox.

Both illnesses are caused by the varicella zoster virus. The virus is passed along through direct contact with fluid from blisters on the skin of people with shingles. So, if you’ve never had chickenpox, you can get it from someone with shingles.

Taking special precautions can lower the risk of transmission. If you have shingles, keep your blisters covered with a non-stick dressing, avoid touching or scratching your rash, and wash your hands frequently to prevent the spread of the varicella zoster virus.

Shingles isn’t infectious until blisters appear. And it’s not contagious anymore once the blisters have formed a crust. But the recovery period can take weeks.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises people with active shingles to stay away from people who have never had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine, especially pregnant women, and individuals with weak immune systems, including people undergoing chemotherapy or taking immune-suppressing drugs, people with HIV/AIDS, and organ transplant recipients.

Getting vaccinated against chickenpox and shingles can reduce your risk of contracting the varicella zoster virus.

Shingles vaccine

There’s no vaccine to treat people who have shingles. But there is a vaccine to help prevent it.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a live zoster vaccine, marketed under the name Zostavax, in 2006. A single dose of vaccine is recommended for most people 60 and older, whether or not they have already had shingles. In clinical trials, the vaccine cut the risk of shingles by half. The vaccine was even more effective in reducing the risk of postherpetic pain that lingers after shingles has disappeared.

Even people who develop shingles after getting the vaccine benefit from getting a shot because their illness is likely to be shorter and less severe.

The zoster vaccine is actually approved for adults 50 and older. However, it is not currently recommended for adults 50 to 59. Current evidence suggests the vaccine provides 5 years of protection against shingles in adults 60 and older. People who receive the vaccine before age 60 might not be protected when their risk for shingles and complications are highest.

The vaccine is not recommended for people who allergic to gelatin, the antibiotic neomycin, or any other vaccine components. People with weakened immune systems, including individuals with HIV/AIDS, leukemia, lymphoma, or other lymphatic or bone marrow cancers, or people taking immune-suppressing drugs should not get Zostavax. Neither should women who are pregnant or planning to get pregnant.

What does shingles look like?

Shingles looks as painful as it sounds. Red patches of skin covered in bumps eventually erupt into fluid-filled blisters that ooze before eventually drying out and crusting over. The infected bands of skin typically wrap around one side of the body—left or right. Shingles mostly appears on the torso, face, and neck, but it has been known to pop up on an arm or leg.

People with weakened immune systems often have shingles that stray from the typical band-like pattern. Their shingles may be more widespread.

People with severe cases of shingles may see permanent changes in the pigmentation of their skin once their blisters scab over and fall off.

How long does shingles last?

An episode of shingles generally lasts two to six weeks. The first inkling that something’s not right may come days before any visible evidence of the infection. You’ll have itching, tingling, or intense pain across a strip on skin on one side of the body. Days later, a rash appears, usually in a single stripe across the left or right side of the torso or face. (In rare cases, people can have shingles without developing a rash.) You may have a headache, fever, chills, or nausea. Fluid-filled blisters begin to appear and continue forming for a few days. It can take five to 10 days before the blisters dry out and form scabs.

Shingles usually strikes just once, but sometimes people have it two, even three times.

Prevention

If you’ve had chickenpox, you may be at risk of getting shingles, especially if you are 60 or older. But you can minimize your risk by getting a shingles vaccine.

The varicella zoster vaccine, marketed under the name Zostavax, has been shown to lower the risk of developing herpes zoster (also known as shingles) by more than half. Among those who develop shingles despite getting a shot, the infection lasts for a shorter period of time, and symptoms are less severe. The risk of postherpetic neuralgia, a painful complication of shingles, is reduced by 67%.

The vaccine is recommended for most adults 60 years and older, even those who have already had shingles because it can ward off a repeat occurrence. It is not recommended for people with allergies to certain vaccine ingredients, those with weakened immune systems and women who are pregnant or planning to get pregnant. And it is not a treatment for people with active shingles.

Adults who have never had chickenpox can protect themselves from chickenpox—and the future possibility of shingles—by getting the varicella, or chickenpox, vaccine. The two-dose immunization is 90% effective in preventing chickenpox. Even if you contract chickenpox, your case will be milder.

Studies show children who receive the chickenpox vaccine have a lower risk of developing shingles. However, it remains unclear whether people who get the chickenpox vaccine as adults have a lower risk of shingles.